Athens Before Thera: The Acropolis, what can it tell us?

Introduction

For those who take Plato’s words seriously it is widely held that the Minoan eruption of Thera marks the end of the war between the Athenians and Atlanteans. And it’s agreed by almost everyone that this eruption is the one pivotal event that turned the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean world upside-down. This more than matches the magnitude of Plato’s description.

Plato’s portrayal of the destruction of a Middle Bronze Age Athens–“in a single day and night of misfortune’ when ‘all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth”—is descriptive of a catastrophe, the scale of which can be understood by modern seismologists and witnessed by anyone through the mass media. Catastrophic events in the Central Americas being a case in point. Liquefaction and land-slides of massive proportions carrying everything away would account for the loss of any archaeological evidence of a MBA Athens. Possible evidence for such an event has shown up in core samples taken from the Piraeus area and as far away as the Levantine and Egyptian coasts. In consideration of Plato’s story, this fact seems to have been ignored by wide sections of the academic community despite the fact that there is a puzzling archaeological gap of about 2400 years in an area that would logically have been rich in archaeological finds. My contention is that the signs of these 2400 years of habitation were swept away by events related to the Minoan eruption of Thera c 1620 BCE and that evidence can be found in abundance in the coast and seabed of Phaleron Bay.

Setting the scene

Louise Schofield in her book The Mycenaeans (2007) presents evidence of a burgeoning Early Bronze Age mainland Greek society that came to a violent end around 2300 BCE. This culture of small isolated settlements–some of which were fortified–grew out of the preceding local Neolithic expansions. According to Schofield, “widespread violent destructions of an established way of life were followed at some sites by what may be the arrival of new people bringing with them their own objects and technology. The closest parallels for the material culture of these new people are to be found in Anatolia (modern Turkey).” It can thus be argued that there was a developing mainland Greek civilisation which was destroyed as peoples from the East encroached onto the mainland, and given the location and time-frame, these invaders could logically be identified as Cycladic and Proto-Minoans of the Early Bronze Age (EBA). This possibly presents one reason for a long lasting Middle Bronze Age war. Plato, an Athenian, was of course sympathetic to Athens–with Aegean connections–in his story while vilifying the Atlanteans as foreigners but, as everyone knows, history is written by the victors. The trouble is, that by Plato’s time, there would have been confusion over identity, resulting from cultural mixing over hundreds if not thousands of years.

If we look to the north and west during this period, we will see the development of sophisticated bronze weapons in the context of the growth of groups led by militaristic war-lords spreading their influence all the way to Britain and down into the Balkan Peninsular. I suggest that the evidence for events resulting from the mixing and confrontation between these groups was swept away ‘in a single day and night of misfortune’.

Geology: questions and clues

It’s difficult to believe that the Athens region was only sparsely occupied during the MBA given its location on the Saronic Gulf opposite the island of Aegina when so many other coastal sites were being developed by people from the East via the Aegean Sea. So for this writer, the apparent paucity of evidence for this period creates a logical problem that can only be sensibly explained by something like Plato’s catastrophe.

In “Piraeus, the ancient island of Athens: Evidence from Holocene sediments and historical archives” by Jean-Philippe Goiran, et al, wrote concerning changes to the coastline adjacent to the port of Athens. One point of great interest to the present discussion is that the course of the Ilissos River changed very rapidly. From about 6700 BC there appears to have been little change; however, at some time in the Middle – Late Helladic period, the course of the river changed dramatically (Goiran et al, 2011). If this change was the result of slow geological morphology, one would expect to find gradual changes in the river’s course; but if, on the other hand, there was a sudden change with no trace of intermediate stages, it would be logical to assume a sudden disruptive event. If there was such an event that could be dated to around the end of the Middle Bronze Age or a bit later it might well be the disaster spoken of by Plato in Timaeus and Critias.

In his monograph, ‘The Athenian Acropolis’, Jeffrey Hurwit (1998), suggests Plato’s description is fanciful on the ground that the spaces between the limestone capped hills of the Athenian plain were formed in the Miocene epoch, 23 million to 5.3 million years ago. He ends his introduction to his book with the words; “the Acropolis is basically an ancient mountain top, a remnant of a once much greater limestone formation that, like the other hills of Athens, came to be partly buried by the levelling sediments that created the Athenian plain.” This is possibly true. But the question is, how much sedimentation was laid down, and how much of the underlying marls might still have been in place by the time of the Middle Bronze Age to be swept away by the Thera event.

My feeling is that more definitive proof of Plato’s Middle Bronze Age Athens is to be found in the region of Phaleron Bay.

Plato and archaeology

A close look at the subtleties of the following translations can support an earlier date than the 12th century BCE as proposed by St. P. Papamarinopoulos in his (2008) paper “Plato and the seismic catastrophe” where he expresses the view that some “analysts of the past have mixed Plato’s fabricated Athens presented in his dialogue Republic with the non-fabricated Athens of his dialogue Critias”, and that “this serious error has deflected researchers from their target to interpret Plato’s texts efficiently.” There is good reason for this view, because Socrates’ discussions in the Republic are conspicuously hypothetical, whereas in Timaeus and Critias, Plato declares Critias’ story to be true, and Timaeus’ offering is intended as a truthful and knowledgeable account of the nature of existence as he understood it. Arguably, in Critias, Plato attempted to bring an important chapter in the prehistory of Greece into the realm of written history. To ignore these aspects of the dialogues, is to render them devoid of credibility, which seems entirely unjustified.

Prof. Papamarinopoulos goes on to argue that Plato, in Critias, used stories, either written or oral, that described a massive destruction of Athens at the end of his Atlantean war. This is a conflation with Homer’s war of the Mycenaeans against Troy in the 12th century BCE. Archaeological finds on and around the Acropolis bear some similarities to Plato’s description. The evidences alluded to are; the remains of an extensive palace on the rock of the Acropolis; soldiers’ residences on the northern slope of the Acropolis; and a deep-cut access to a dried-up spring at the foot of the Acropolis that was strewn with Mycenaean artefacts, indicating the final use of the spring at that time. Other evidence is gleaned from the seismic history of the Aegean Sea and its surroundings which indicates wide-spread devastation early in the 12th century BCE, but evidence suggests this destruction was not necessarily the case for Athens which, according to Louise Schofield ‘may have escaped relatively unharmed by the destructions of 1200 BC.’ (Schofield, 2007).

Evidence of Mycenaean habitation on the Acropolis is not in question, but there are inconsistencies in matching these finds with Plato’s description but the idea of linking the timing of Plato’s Atlantean war with Homer’s Trojan war is, for me, extremely doubtful.

Plato’s reference to the “dwellings round about the temple”, and “surrounding themselves with a ring fence, resembling that of a single dwelling” suggests that there was a fence around the combined complex of dwellings and temple, and that it was something far less imposing than the massive existing cyclopean retaining wall around the Acropolis which was built by the Mycenae where the soldiers’ dwellings were found outside the great wall, on the slope, not on top of the Acropolis. Also, traces of a large Mycenaean structure near the Propylaea have been described by archaeologists as the remains of a palace, which one would assume to be vastly different from a temple, as referred to by Plato. This, however, is only part of the picture.

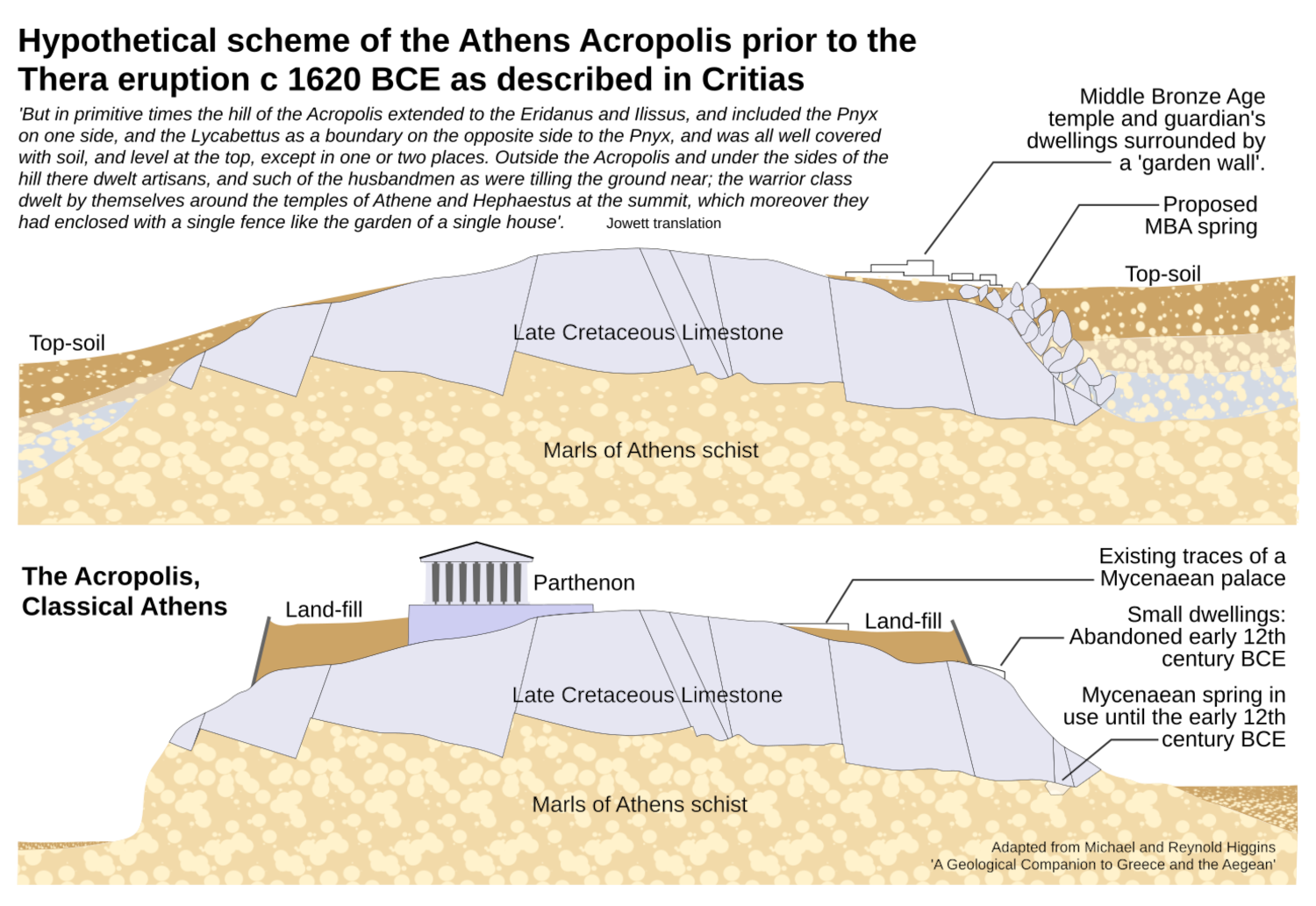

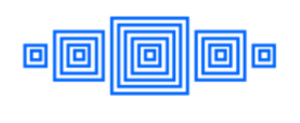

The following passage gives a fairly detailed description of the hill of the Acropolis on which the military class lived at the time of Plato’s Atlantean war:- “Now the city in those days was arranged on this wise. In the first place the Acropolis was not as now. For the fact is that a single night of excessive rain washed away the earth and laid bare the rock; at the same time there were earthquakes, and then occurred the extraordinary inundation, which was the third before the great destruction of Deucalion. But in primitive times the hill of the Acropolis extended to the Eridanus and Ilissus, and included the Pnyx on one side, and the Lycabettus as a boundary on the opposite side to the Pnyx, and was all well covered with soil, and level at the top, except in one or two places.*Outside the Acropolis and under the sides of the hill there dwelt artisans, and such of the husbandmen as were tilling the ground near;” (Benjamin Jowett, translation c 1864-1871).

*This implies that some of the rock was exposed prior to the devastation. At least one cave on the side of the rock suggests use that dates back to the early Neolithic, but this does not necessarily negate Plato’s over-all description.

This clearly defines the Acropolis as a soil-covered hill bounded by the Eridanus and Ilissus rivers and the landmarks mentioned, the Pnyx and the Lycabettus. It therefore logically follows that the Mycenaean archaeological finds still remaining on the Acropolis post-dates Plato’s devastation when, in a single night all the soil was stripped away, leaving the Acropolis rock exposed. And, if Plato’s information was correct, the temple, the dwellings, the people and their artefacts were swept into oblivion. In the final analysis, Plato’s guardians of Athens were living atop the Acropolis hill at the time of the destruction. This would need to have been before the Mycenaeans built their palace and dwellings there, when it appeared pretty much as Plato would have seen it. If the Acropolis was a hill bounded by the rivers as mentioned above, it would have been extensive, with the rock of the Acropolis being a relatively small component.

The population of a Middle Bronze Age Athens is unknowable but perhaps this might be estimated by considering the ratios of military to civilians within historic populations. Plato gives the number of military personnel as follows:- “And they took care to preserve the same number of men and women through all time, being so many as were required for warlike purposes, then as now–that is to say, about twenty thousand.” (Jowett translation, c 1864-1871).Under the ‘Middle Bronze Age hypothesis’, twenty thousand (20,000) should be corrected to two thousand (2000). This is still a considerable fighting force. Even if the military comprised as much as 10% of the general population, the casualties from the Thera event could hypothetically have been as high as 20,000 individuals.

If we compare Plato’s description of the hill of Athens, with soil so deep as to cover the rock of the Acropolis, as depicted in the top drawing of figure 2, (below) and if we take the cross-section as depicted in the bottom drawing of figure 2, as representing the present configuration of the Acropolis, then the loss of soils and marls of schist must have been enormous. It is of course possible that this erosion took place over a period of time, but if most of it happened in one dreadful day and night as Plato said, then the annihilation of everyone and everything on the hill at that time, must have been total and beyond imagining.

Translations of the dialogues, such as those of Waterfield, Jowett and Lee, say pretty much the same thing: “[T]here was a single spring in the area of the Acropolis” (Waterfield, 2008); “[W]here the Acropolis now is there was a fountain” (Jowett, c 1864-1871.); – “[T]here was a single spring in the area of the present Acropolis” (Lee, 1965). All the translations seem to suggest the rock of the Acropolis was not an overly prominent part of the landscape at the time referred to by Plato. Under this scheme, the fountain/spring could very likely have been in a rocky outcrop that was part of the now exposed rock of the Acropolis. If we imagine a hill without the Acropolis rock being exposed–at least, not entirely; and there was a spring supplying abundant water at the site of the rock, earthquakes and torrential rain then destroyed the prehistoric Acropolis in the event described by Plato, the resulting landslides could have blocked the spring, resulting in a few small streams.

On the north-western slope of the Acropolis, about 4-5 m above the Klepsydra, the Mycenaeans constructed stairs to access a water source which appears to have been used for about 25 years before it was abandoned. The “[f]low from these springs was probably stronger in antiquity. This may reflect climatic change, but is more strongly controlled by modifications to the geography of the hill. In the past the presence of plants, soil and loose materials on top of the bedrock would have retarded run-off so that the water could have time to be adsorbed” (Higgins and Higgins, 1996). If a strong capacity for water catchment was dramatically reduced in the manner described by Higgins and Higgins, by way of a geological catastrophe, this would certainly apply to an event such as that described by Plato.

Plato and his forebears display a remarkable knowledge of how the water supply worked in the context of the geography of Attica. In Critias he describes the loss of the good soil of Attica due to erosion. ‘Many great deluges have taken place during the nine thousand years, for that is the number of years which have elapsed since the time of which I am speaking; and during all this time and through so many changes, there has never been any considerable accumulation of the soil coming down from the mountains, as in other places, but the earth has fallen away all round and sunk out of sight. The consequence is, that in comparison of what then was, there are remaining only the bones of the wasted body, as they may be called, as in the case of small islands, all the richer and softer parts of the soil having fallen away, and the mere skeleton of the land being left‘.…‘Moreover, the land reaped the benefit of the annual rainfall, not as now losing the water which flows off the bare earth into the sea, but, having an abundant supply in all places, and receiving it into herself and treasuring it up in the close clay soil, it let off into the hollows the streams which it absorbed from the heights, providing everywhere abundant fountains and rivers, of which there may still be observed sacred memorials in places where fountains once existed‘ (Jowett translation). It can be reasoned that in this way prehistoric Athens’ water supply was severely diminished at a time before Mycenaean occupation in the LBA.

The Fallout from Thera

Athens

The Saronic Gulf would not have been exposed to the direct power of a tsunami generated by the eruption because many of the Cycladic islands, Sikinos, Pholegandros, Poliagos, Melos, Kimolos, Siphnos, Seriphos and Kynthos were directly between Thera and the Saronic Gulf. Conventional wisdom says, the tsunami was generated from the south-western rim of the island and is thought to have travelled in that general direction. But earthquakes, rain, liquefaction, massive mud and land slides are certainly on the cards.

If we were to accept Plato’s description of the event as valid, and we want to envisage events as they might have happened, we have plenty of material available to us through modern day mass media. Images are available to us of large scale catastrophes throughout the world, such as mud slides in Chile, the devastation of earthquakes around the Mediterranean and in the Indonesian Archipelago. Below is a hypothetical scheme of what the effects might have looked like at Athens.

The questions raised by Melanie Harris in her 2016 thesis gives rise some rather interesting notions that pose some serious questions about the state of the Athens plain after Thera’s eruption. The fact that Mycenaean development at Athens did not occur until c 1450-1400 BCE (Harris, 2016)–at least 160-200 years after the eruption and later than any other mainland development–was, I propose, due to the Athenian plain being uninhabitable and it might have taken that long for the region to regenerate.

In reference to the early LBA geopolitical state in southern Greece, Papadimitriou and Cosmopoulos (2020) make the point that although ‘changes are well documentedfor areas such as the Argolid, Messenia or Boeotia,this is not the case with Attica, whose socio-politicalorganization remains hazy‘. Other references are made to the archaeological evidence found throughout the region that demonstrate the course of event from the Early to Late Helladic periods. Particular reference is made to Eleusis which was occupied from the beginning of the MBA and kept growing into the LBA so it seems not to have suffered to the same extent as its close neighbour, Athens. Thorikos on the south-eastern coast of Attica–probably due to its wealth in silver and lead–seems to have thrived throughout the MH III until the LH IIA with strong links to the Cyclades and with evidence of large quantities of pottery from Aegina but Minoan pottery is very rare.

There are a few traces of Middle Helladic presence at Athens but they are mostly at the extremities of the Athenian plain. Nozzles from bellows and ceramic kilns have been found at Athens. The question needs to be asked; why would there be only scraps of evidence for occupation at Athens?

According to Papadimitriou and Cosmopoulos (2020), ‘Middle Helladic traditions survived for long in Attica and it was only in LH IIB-IIIA1 that the region started to become ‘Mycenaeanized’’ (Papadimitriou and Cosmopoulos, 2020).

Spyros E. Itakovidis (2006) in writing about the Mycenaean building works on the Athens Acropolis in Late Helladic times, notes the distinct similarity to the fortifications at Mycenae and Tiryns on the Peloponnese. He claims that all three mentioned were built at roughly the same time with the qualification that Mycenae and Tiryns both displayed developmental techniques, whereas ‘[d]espite a slow beginning, the Acropolis of Athens shows a sudden application of these principles in fully developed form‘. This scenario fits well with the idea that the mainland Mycenae took some time to recover from the devastation wrought by the eruption and to establish itself with some sense of power (Itakovidis, 2006).

Crete

The impact of the Minoan eruption of Thera and the resulting tsunami can hardly be questioned as the visible effects have been examined and reported upon by innumerable researchers and scholars–too many to mention–but this is not so for the later presence of Helladic mainlanders on Crete. There is a great deal of controversy around the process and nature of the Mycenaean ‘invasion’, but it is widely held to have occurred around 1400 BCE, roughly about the time, or slightly later than the earliest signs of Mycenaean developments at the Agora of Athens. The delay in their habitation of Athens could have been due to the above-mentioned destruction of a more ancient Athens or perhaps there was a correlation between the decline of Minoan influence and the rise of the Mycenae. Both processes were probably at work. Perhaps the best guide to the timing and nature of a take-over can be found in the widely used Linear texts.

Linear A shows up on Crete and some Aegean Islands around 1850 BCE until about 1400 BCE. The Mycenaean Linear B dates from about 1600 BCE to the end of the Mycenaean period c 1200 BCE (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Linear-A, 2024). The appearance of Linear B only about 12 or so years after the Thera eruption is interesting in view of the fact that many scholars date the mainland ‘invasion’ of Crete to about 1400 BCE, almost 200 years after the emergence of Mycenae as a distinct entity. This suggests a prolonged period of contact before the Mycenaean culture gained prominence within the whole region.

Argolis and Laconia

There is a paucity of information about the affects of the Thera eruption on the southern Peloponnese. Almost certainly this area would have–unlike Athens and the Saronic Gulf–been exposed to the full force of a tsunami generated by the eruption. This can be seen in the modelling of the event by (Novikova-Papadopoulos-McCoy, 2011).

Scheffers, Kelletat, Vött, May and Scheffers, (2008) state that although the Minoan eruption of Thera was one of the most extreme volcanic events world-wide, ‘[t]o date, field evidence on land for this event is missing‘, and that evidence at only 16 sites have been found so far. They found signs of tsunami impact ‘in the form of clusters and ridges of large boulders and thicktsunamigenic sand layers’. The best form of evidence is in the movement of large boulders which Scheffers et al. have found at sites on the coasts of Laconia and Messenia in the Peloponnese where there has been no deltaic deposition of silt to cover any existing evidence. This seems to be the main reason why no direct evidence of the event has been found in the Gulf of Argolis which would seem to have received the full force of a tsunami generated at Thera.

Konstantin Ntageretzis cites Papazachos and Dimitriu (1991), saying ‘southeastern Peloponnese is exposed to a high tsunami hazard‘ (Ntageretzis, 2014). This means that southern Peloponnese would have been fully exposed to a tsunami generated by the west/south-western caldera collapse as modelled by Novikova, Papadopoulos and McCoy (2011). This is a very important point when considering Plato’s assertion that the fighting men of the Atlanteans were swallowed by the sea, given that any war waged against Athens would have been best affected from the eastern Peloponnese; which makes sense in the light of an eventual occupation of the Peloponnese by the allies of the Mycenae.

Discussion

It is interesting that the finding of Mycenaean structures and artefacts on the Acropolis puts the occupation date for Athens back 400 years before the previously believed date of 800-900 BCE. Even so, to have no evidence of occupation before the 13th or 14th centuries seems very suspicious, particularly, when there is evidence for Minoan MBA activity on the nearby island of Aegina. This strongly implies an almost total erasure of any occupation of Athens some time before the Mycenaean era. With this in mind, I believe that Minoan and Cycladic artefacts are still to be found buried in and around Phaleron Bay below Athens.

Ring-seals and other artefacts at Mycenae

The ring-seals and other artefacts found in the early Grave Circles of Mycenae which are generally dated c 1600-1500 BCE (projectsx.dartmouth.edu Revised 2000 ), within 100 years after the Thera eruption. This means they can be placed at the very earliest stages of the Mycenaean culture. Given that the events illustrated on the grave objects must be prior to the burials, and after the events they depict means that if these images are of Plato’s war, then it occurred in the 17th century and not the 12th century BCE. It should be noted that the weapons depicted in the “battle scene” ring seal, perfectly reflect Plato’s description.

Radiocarbon Dated to 1627-1600 BCE

Dating of the Grave Circles, relative to dating for the eruption has in the past, been a little bit fuzzy, but not inordinately so. But now, a recently published article on the website of Science, “Santorini Eruption Radiocarbon Dated to 1627-1600 BCE” by Walter L. Friedrich et al. (2006), gives a very precise date for the eruption. The abstract reads as follows:- “Precise and direct dating of the Minoan eruption of Santorini (Thera) in Greece, a global Bronze Age time marker, has been made possible by the unique find of an olive tree, buried alive in life position by the tephra (pumice and ashes) on Santorini. They used ‘radiocarbon wiggle-matching‘ against tree-ring segments to date a range from 1627‐1600 BCE with 95.4% probability. This puts the date a century earlier than that derived from traditional Egyptian chronologies.

Conclusions

The lack of evidence for a Middle Bronze Age Athens has ensured that there has been little speculation as to its existence by the academic community; at least, not that I’ve seen. But for this hiatus to exist in the context of the MBA should be considered suspicious to say the least in the light of all the activity going on in the area at that time.

It’s difficult to understand why Plato’s story has not been examined more closely in recent times given that we now know so much about seismic and volcanic events and the resulting consequences of big events such as described in the Critias dialogue. We know about liquefaction and land-slides and how they work; so why has there not been any investigation in the area where the evidence must lie–beneath Phaleron Bay. Therefore, the event when the fighting men of Athens were ‘swallowed by the earth‘ occurred before the Mycenae had become a recognisable culture. The great majority of questions relating to Plato’s story can best be answered by a MBA hypothesis, so I must stand firm on placing Plato’s war immediately prior to the eruption of Thera, towards the end of the 17th century BCE.

Cultural and technical developments in Western Europe and North Africa from the Neolithic to the Middle Bronze Age, can be seen as a pan-western phenomenon that reached its peak expression in the Beaker Burial cultures. By placing the events of the Atlantis war around the time of the Minoan eruption at Thera, most aspects of the story can be resolved as they fit more consistently with archaeological findings, and what is known about the late prehistory of Europe and the Mediterranean.

Theories that focus on only one or two features of the story and ignore all other assertions and descriptions presented by Plato, in my opinion, are left wanting. Only when most aspects of the story come together to present a coherent, sensible picture that corresponds to the rest of known history, can we assume that we are fairly close to the truth, perhaps resolving the questions posed by Plato’s amazing story.

References – Resources

Apollodorus, The Library of Greek Mythology, translated by Robin Hard, (1997). Oxford World Classics, Oxford, pp. 37, 58, 68, 73-84, 115, 132.

Apollonius of Rhodes, The Voyage of the Argo, trans. E.V. Rieu, (1959). Penguin Classics, GB, pp. 37, 38.

Barfield, L.H. (March, 1991). Wessex with and without Mycenae: new evidence from Switzerland. Antiquity. Vol. 65 No. 246 , pp. 102-107.

Beck, Julien, Patrizia Birchler Emery and Despina Koutsoumba, 2023, A Submerged EH II Settlement at Lambayanna in the Argolid:the Preliminary Results of the 2015 Survey1

Boulona, Julien, et al, Observations of nucleation of new particles in a volcanic plume, abstract from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2011/06/30/1104923108.

Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, (1901). A map of ancient Athens. Uploaded by Jan van der Crabben. http://www.ancient.eu.com/image/134/ Ancient History Encyclopedia

Broneer, O. (1939). A Mycenaean fountain on the Athenian acropolis, Hesperia 8, p.p. 317-429.

Broneer, O. (1948). What happened at Athens, American Journal of Archaeology 52, p.p. 111-124.

Chadwick, John (1990). The Decipherment of Linear B, Cambridge University Press, Canto edition, Cambridge, p. 44.

e-friend (1997).The Odyssey in Linear B: Commentary from e-friend in the Netherlands, e.pantos, http://srs.dl.ac.uk/people/pantos/leiden_jan25.html

Dartmouth College, (Revised 2000). Lesson 16: The Shaft Graves. The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean. (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/16.html)

David, Rosalie, Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File, Inc. NY, revised edition, 1998. p.158.

Friedrich, Walter L.; et al. (28 April 2006). Santorini Eruption Radiocarbon Dated to 1627-1600 BCE Science www.sciencemag.org, Vol. 312 no. 5773 p. 548, DOI: 10.1126/science.1125087

Gauss, Walter, and Rudolfine Smetana, March 2006, Aegina Kolonna in the Middle Bronze Age, BCH – Mesohelladika, Supplement 52, pp. 165-174.

Grant, Michael (1988). The Ancient Mediterranean, Meridian, Penguin Books, New York, pp.133-134.

Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths, vols I and II, Pelican Books, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, pp. 388, 391.

Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt, translated by Ian Shaw, Blackwell, UK, 1992. pp. 51, 52.

Gronenborn, Detlef, 2008, Early pottery in Afroeurasia – Origins and possible routes of dispersal, Early Pottery in the Baltic – dating, origin and social context international Workshop at schleswig from 20th to 21st october 2006, Bericht der Römisch-GeRmanischen Kommission band 89 , 2008, pp. 59-88.

Hepke, Juergen Karl, Atlantis in Puerto de Santa Maria/Cadiz/Spain, Book of Abstracts & Program, Atlantis Hypothesis International Conference 2011. p.12.

Herodotus, The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt (1954), Penguin Classics, Middlesex, pp. 61, 333.

Higgins, Michael and Reynold, -Excerpt from Chapter 3, Attica, of ‘A Geological Companion to Greece and the Aegean’, (1996). http://depcom.uqac.ca/~mhiggins/athen.htm

Homer, The Iliad, translated by E. V. Rieu (1978). Penguin Books, Middlesex. Passim.

Homer, The Odyssey, translated by E. V. Rieu (1979). Penguin Books, Middlesex. p. 25.

Huebner, Michael and Sebastian, New Significant Evidences for Plato’s Island Atlantis in the Souss-Massa Plain in today’s South-Morocco, Book of Abstracts & Program, Atlantis Hypothesis International Conference 2011. p.12.

Heyd, Volker 2007, Families, Prestige Goods, Warriors & Complex Societies: Beaker Groups of the 3rd Millennium cal BC Along the Upper & Middle Danube, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 73, pp. 327-379

Ingram, Don (2009). The Unlost Island: a History of Misunderstanding Atlantis, Zeus Publications, Qld. Aust. p. 275, 192-201, 292, 296, 305-310.

Itakovidis Spyros E. 2006, Epilogue 2. The Acropolis of Athens in Relation to the Other Mycenaean Citadels, The Mycenaean Acropolis of Athens,. The Archaeological Society at Athens Library No 240 Athens 2006

James, T. G. H., Pharaoh’s People: Scenes from life in imperial Egypt. The University of Chicago Press. 1984. p.29.

Kelder, Jorrit M. (2010) The Egyptian interest in Mycenaean Greece, Annual of Ex Oriente Lux (JEOL), (p. 128). http://uva.academia.edu/JorritKelder/Papers/153778/The_Egyptian_Interest_in_Mycenaean_Greece#

Maran, Joseph (post 1994), Structural Changes in the Pattern of Settlement During the Shaft Grave Period on the Greek Mainland.

Mitropetrou E. P. The Four Main Questions of the Platonic Logical Myth of Atlantis, Part II: Why Plato presents this myth as a preamble to the logical Myth of Timaeus on the creation of the world? Which was the effect of the Atlantis Myth on subsequent researchers? Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on “The Atlantis Hypothesis” (Atlantis 2008) Athens Greece. pp. 61-71.

Novikova, T., G. A. Papadopoulos and F. W. McCoy, 2011, Modelling of tsunami generated by the giant Late Bronze Age eruption of Thera, South Aegean Sea, Greece. Institute of Geodynamics, National Observatory of Athens, 11810 Athens, Greece.

Ntageretzis, Konstantin 2014, Dissertation, Palaeotsunami imprints in the near-coast sedimentary records of the Gulfs of Lakonia and Argolis (Peloponnese, Greece) Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, 2014

Papadimitriou, Nikolas and Michael B. Cosmopoulos 2020, The Political Geography of Attica in the Middle and the Late Bronze Age, Αthens and Attica in Prehistory, Proceedings of the International Conference, Athens, 27-31 May 2015, Archaeopress Archaeology 2020.

Papamarinopoulos, Prof. St. P. Plato and the seismic catastrophe in the 12th century BCE Athens. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on “The Atlantis Hypothesis” (Atlantis 2008) Athens Greece. pp. 73-87.

Pernigotti, Sergio, in The Egyptians, edited by Sergio Donadoni, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1997. pp. 130, 132-133, 139-140.

Plato, Critias, translated by Benjamin Jowett (c 1864-1871.) http://classics.mit.edu/Browse/browse-Plato.html

Plato, Timaeus, translated by Benjamin Jowett (c 1864-1871.) http://classics.mit.edu/Browse/browse-Plato.html

Plato, Timaeus and Critias, translated by Desmond Lee (first published 1965). Penguin Books, Middlesex, pp. 132 134.

Plato, trans. Robin Waterfield (2008) Timaeus and Critias, Oxford University Press, Oxford New York. pp. 109-110.

Renfrew, Colin (1968). Wessex without Mycenae, The Annual of the British School of Athens, No. 63, pp. 277- 285.

Rutter, Jeremy B (2011) lecture notes, http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/16.html

Scheffers, Anja, Dieter Kelletat, Andreas Vött, Simon Matthias May, Sander Scheffers,. Late Holocene tsunami traces on the western and southern coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece)

Schofield, Louise (2007) The Mycenaeans, Getty Publications, LA, pp. 25-26, 184.

Seach, John (2012), Volcanic Rain, Volcano Live, http://www.volcanolive.com/rain.html

Shepherd, William (1923-26) Historical Atlas, reference map of Attica 480 BC. Kent, Emerson, History for the relaxed historian. http://www.emersonkent.com/map_archive/attica_480_bc.htm

Stos-Gale, Zofia A. and Noel H. Gale, 2010, Bronze Age metal artefacts found on Cyprus – metal from Anatolia and the Western Mediterranean, TRABAJOS DE PREHISTORIA 67, N.o 2, julio-diciembre 2010, pp. 389-403, ISSN: 0082-5638 doi: 10.3989/tp.2010.10046

Stubbings, Dr. Frank (1994). Greece and the Aegean. Atlas of Ancient Archaeology, edited by Jacquetta Hawkes. Michael O’Mara, London, pp. 113-115.

Tyldesley, Joyce. Pyramids: the real story behind Egypt’s most ancient monuments, Viking, UK, 2003. p.p. 73-77.

Vander Linden, Mark M., 2004, Polythetic Networks, Coherent People: A New Historical Hypothesis for the Bell Beaker Phenomenon, Similar but Different. Bell Beakers in Europe , edit. Czebreszuk J. (ed.) , Poznañ, pp. 35-62.

Vermeule, Emily and John Travlos, 1966, Mycenaean Tomb beneath the Middle Stoa. Reprinted from ‘Hesperia’; Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Published by Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 1966.