“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new

landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

– Marcel Proust

Overview

It’s tempting to think the Greek myths and legends belong only to the Greeks but even a cursory reading of these stories takes us back to the earliest times in and around the Fertile Crescent, Anatolia and the Circum-Pontic region. Even influences from the Indian sub-continent would have widely affected events in the Fertile Crescent via the Iranian Plateau and Southern Mesopotamia.

There can be little doubt the ancient stories that have come down through time–about people who lived West of the Sub-continent–had their origins in this sphere where continents meet. The Epics of Mesopotamia, the Levantine Biblical stories and what came to be known as the Early Greek legends were all generated from interactions between the diverse groups that came into contact following the end of the Ice Age during the Holocene era. This being the case, we do ourselves a gross disservice by isolating these traditions from each other. There are many conspicuous overlaps in all these traditions and the main focus here is on the Greek traditions as well as the stories of events that feed into the formation of Greece as a defined culture.

Among these traditions is Plato’s story of a war between Athenians and Atlanteans which has, ever since its inception prompted controversy, and often vehement and irrational argument even to the present day; which of course means the question of the veracity of Plato’s story has never satisfactorily been resolved. I wish to show that this story, as told in Timaeus and Critias (T&C) is strongly supported by archaeological evidence and that the main reasons for the unresolved, on-going debate can be identified.

Plato was a man of his time; a member of an influential Athenian family, erudite and well resourced. He would have had access to most, if not all the extant myths and legends of his culture. If we look at these stories and make allowances for all the inherent exaggerations, biases, poetic devices and symbolism, and concentrate on the essential information contained therein, we may recognise the actual events and people about whom they are told. These stories would have provided Plato with background material to flesh out the story provided by Critias for his writing of the T&C dialogues.

A debate about the actual existence of Plato’s island has to start with the assumption that he believed the story was of real events handed down over time. On the other hand, if we assume Plato meant the story as an allegory, this renders any further discussion on the veracity of the story void and pointless. The mandate then, is to test the contents of T&C against what we can reasonably assume about the course of prehistory at the frontier between the Middle and Near East, and Europe. Also, we must accept the premise that the understandings of ancient writers such as Plato were subject to the limitations of their world-views–as we all are–so what they wrote must not be considered immutable or immune to criticism and correction; the trick is to recognise what can be determined as true and what is error.

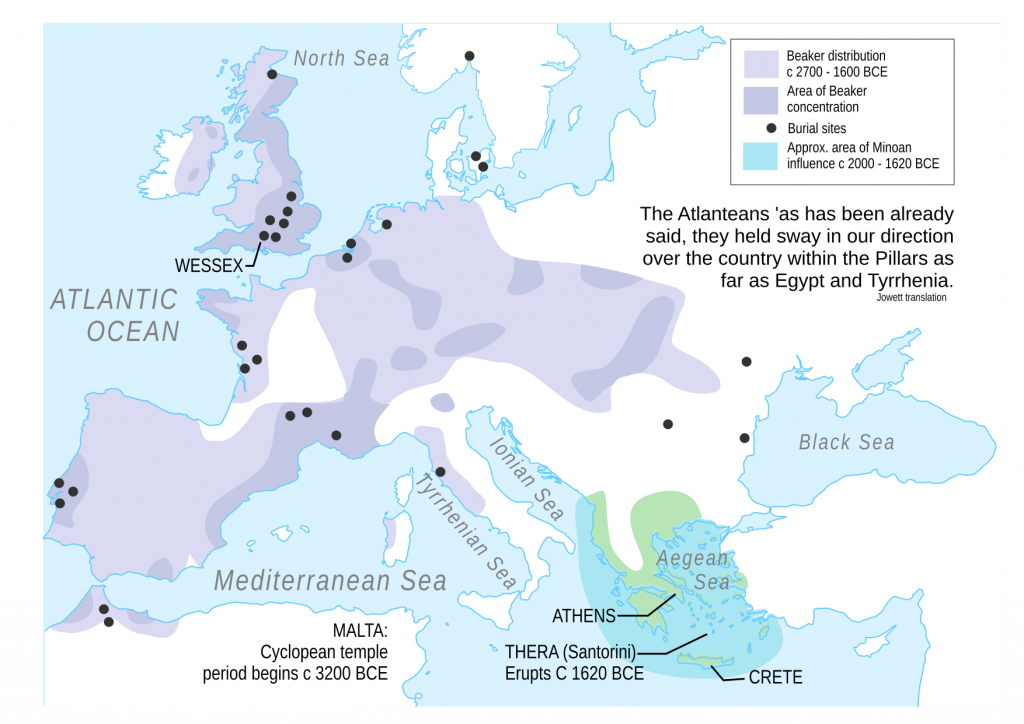

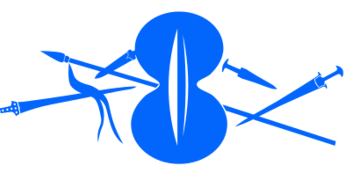

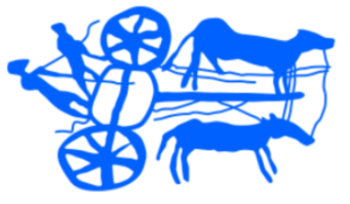

Under the present hypothesis, the story told in T&C, fits into a period when peoples from western Anatolia via the Aegean Sea islands–the Cyclades in particular–established themselves on the Greek mainland, at the turn of the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age (EBA). It was from the perspective of these people, that the story seems to have been told. The “arrogant Atlanteans” entered the story toward the end of the EBA, kick-starting the Middle Bronze Age (MBA), bringing with them their funerary customs of semi-cist and shaft grave burials, the Grey Minyan-type pottery and their devastating new weapons–rapiers, swords, halberds, and horse-drawn chariots. These peoples might be thought of as the proto-Mycenaeans.

If we strip away all the extant hypotheses, pre-conceived ideas, ‘received wisdoms’ and assumptions, and concentrate solely on the story told through the available evidence of archaeology and its associated sciences, we can arrive at a broad-stroke overview–simplistic though it might be–of the events in and around the Aegean Sea from the Early Bronze Age through the Middle Bronze Age and the start of the Late Bronze Age (LBA), concluding with the Minoan eruption of the Thera volcano ca 1620 BCE leading into the Mycenaean era. The well defined archaeological layers at Kolonna on the island of Aegina, not far from Athens, give a particularly clear indication of the push and shove that occurred during this period. Many other sites on the mainland and Euboea seem to tell pretty much the same story but the lack of precise dating tends to confuse the picture somewhat. Viewed through a broad perspective, Plato’s story is a surprisingly accurate description of events in the Middle to Late Bronze Ages in Greece, a period of about 400 years.

Many assumptions have been made about the identities of the various peoples referred to as Greeks; and this needs to be examined. To get some idea of who the protagonists actually were, it will be helpful to go back to the Early Holocene when the world was changing in radical ways, and groups of people who had previously been genetically and culturally isolated for many thousands of years moved and expanded their range of activities, coming into contact and inevitably, conflict.

The science of genetics is particularly helpful in recognising the various ethnic groups; when they diverged and when they came back into contact with each other with some very ‘interesting’ consequences.

The Modern views

Victims of the New-Age movement have long believed this mythical island vanished beneath the ocean, just as Plato said. The survivors of this catastrophe, the remnants of a highly advanced ‘Elder culture’, escaped to the mainlands on either side of the Atlantic giving rise to the high cultures of Egypt and Central and South America, which have been seen as mere echoes of the Atlantean civilisation, from whom they learnt the “civilising arts”. This idea has been soundly discredited by extensive archaeological work, showing widely separated dates between Egypt and the Americas. Evidence of localised development, over time, of these major civilisations on both sides of the Atlantic debunks the whole idea of the sudden appearance of a super culture in these areas.

Stories of fabulous beams of light, so often referred to in various books on the subject of Atlantis and featured in at least one forgettable B-grade film of the fifties, was derived from the psychic readings of Edgar Cayce, ‘the sleeping Prophet’ where he described a large crystal that harnessed the power of the sun and was the central source of power for a sophisticated psychic technology. The stories of these beams of light, may have gained extra credence from a device invented by Archimedes in the third century BCE. This took the form of a highly polished metal hyperbolic reflector that concentrated the sun’s light into a beam that was aimed at enemy ships to set their sails alight. The Greeks are thought to have used these reflectors against the Romans at Syracuse, some years after Plato’s lifetime. Their usefulness must be suspected because the target would need to stay at a fairly constant distance from the device for it to be effective. However, the fact this technology has been taken out of its time, and attached to a time that was considered ancient history by Plato, seems of little consequence to some. There are innumerable examples of atlantologists, on seeing certain ancient artefacts on both sides of the Atlantic have jumped to the conclusion that an unknown superior technology must have been used in their production. The more we learn about past ways of doing things, the less credible these claims become; even though we are constantly being surprised by the ingenuity of our ancient ancestors.

Many alternative sites for Atlantis have been suggested, some of which require extraordinary leaps of imagination and the complete ignore of any practical requirements for the logistics of waging war against the Greeks. This problem had been ‘overcome’ by the invention of impossibly advanced technologies, for which there’s no visible evidence at all. At any rate, one might ask; how could such an advanced race have been defeated by the ancient Athenians?

Some of the most common suggestions for the ‘real’ location of Atlantis have been in North America, South America, the Caribbean Islands, the Azores, the Canary Islands, Greenland and even Antarctica! On the other hand, several scholars such as E. S. Ramage, Sir Arthur Evans, and Professor Spyros Iakovidis have tried to attach the story to places within the Mediterranean Sea, principally the island of Santorini. Crete, Cyprus and all other Mediterranean islands that have been subject to seismic or volcanic activity must also be included as possibilities in a Mediterranean hypothesis. None of these make historical or logical sense: the Minoans along with the Cycladic and Helladic peoples lived, traded extensively and shared cultural influences in this area for a very long time. Homer, in writing the Iliad, claimed the men of Rhodes—the most distant of the Aegean Islands—to be descendants of Hercules. Crete also, was very much a part of Greek mythology, so it seems Plato must have considered the peoples of the Aegean Sea to be part of, or at least related to the Greek world, and therefore, were not foreigners from the distant Atlantic region.

Others, with whom this writer agrees, have proposed the British Isles as a likely site for Atlantis. This suggestion has previously been discounted on the grounds of location and size.

The problem of location may be explained by what’s known about navigation in prehistory; methods developed within the Mediterranean Sea, when applied to the Atlantic Ocean would prove entirely inappropriate. This is the critical key that has been missing for all of the previous supporters of a British Isles, location.

There is some merit in the idea that Plato used events and peoples within his own experience to create a fictional society, but this notion ignores the fact Plato wrote scathingly about the writers of fiction, and in telling his parables and allegories, he always stated how they were meant to be understood.

Context of the Dialogues

Characters of the dialogues were people of prestige and status in Greek history, and were known to Plato. Timaeus, of Locris–a Greek colony in Italy–is the only person for whom there is any difficulty at all in identifying. Critias is almost certainly a maternal uncle of Plato and one of the Thirty Tyrants installed in Athens by the Lacedaemians at the end of the Peloponnesian War. Hermocratese was a highly regarded General of Syracuse on Sicily who was active against Athens and it is believed he was involved in the enslavement of Plato during one of his diplomatic visits to Sicily. And of course, Socrates was one of the great Greek philosophers and Plato’s teacher. All three character had their areas of expertise within the dialogues and they will be discussed further in relation to the Life and Times of Plato. These facts alone should suggest that Plato’s intention was serious and grounded in what was thought to be the best knowledge of the times.

Socrates begins the dialogues by summarising his theories of the ideal society he had presented the previous day to his guests, Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates, and was now to be graced with oratory offerings from his three guests. Timaeus was the first to present his address which comprised a brief introduction to Critias’ story of the exemplary ideal society of ancient Athens before embarking on his own subject of cosmology and the nature of existence as it was understood by the most advanced thinkers of the day. After Timaeus’ presentation, Critias followed with his story of Atlantis which he had learned from his grandfather, who in turn had it from his father, who had been a friend of Solon, to whom he was also related.

It is widely believed that Hermocrates was to have presented ideas on establishing a civilised society at its inception; and that this subject was subsequently dealt with in the “Laws” dialogue. It’s interesting to note that in the T&C dialogues Plato moved his focus away from Hermocrates and Syracuse; whereas in the Laws he turned his attention to a Cretan named Clinias and the creation of a constitution for the new Cretan colony of Magnesia.

Solon, a Greek statesman, reputedly had learnt the story from an old priest when visiting Egypt during the reign of the Pharaoh Amasis, in the mid sixth century BCE. The story describes the origins and nature of the two cultures and how Athens’ enemy, the Atlanteans, became corrupted by greed and power, and for their sins were sent to war against the Athenians by the gods as punishment. Political and military structures and the physical environs are described in detail. It is in these descriptions where the large numbers create problems of disbelief. Time-spans involving large numbers–eight and nine thousand years before the time of Solon–are also deeply problematic.

Context of the Story According to Critias

The time-scale presented by an old Egyptian priest for the histories of Athens and Egypt—between 8000 and 9000 years before Solon’s visit c 600 BCE—causes problems. This time frame takes us back to the late Mesolithic and beginning of the Neolithic period, prior to any settlement resembling a city, almost 2000 years before the oldest layers at Jericho. More importantly, it is 4000 or 5000 years before any known written records which only came into existence with the great civilisations of the Middle East. Spoken tradition would therefore have been the only vehicle for ancient stories from the previous 4000 to 5000 years, and could not have been recorded directly into the Egyptian archives.

The priest told Solon that in their temples they have ‘from earliest times a written record of any great or splendid achievement or notable event which has come to our ears whether it occurred in your part of the world or here or anywhere else’. The ‘earliest times’ during which records began to be kept are generally considered to have been from early dynastic times, not earlier than the mid fourth millennium BCE. It may have been that the priest who spoke to Solon had access to only about 900 years of written history—some time after the beginning of the New Kingdom—following the disruption and dislocation of the second intermediate period when Egypt was ruled by the foreign Hyksos. These 900 years may have been misrepresented as 9000 years and any records before this time would likely have been in the form of fragmentary archives from the various previous dynastic centres of rule.

Reasons for Misunderstandings

In looking for reasons for our difficulty in understanding the story, we would quickly discover the main points of contention are: (1) The location of the island of Atlantis, ‘opposite the strait’ (The Pillars of Hercules); (2) The extraordinarily long time frame given for the institutions of Greece and Egypt; (3) The unbelievable size of the plain on which Atlas’ city was built; (4) Plato always referred to one single, large island in the Atlantic, and this has caused a major problem of identification; and (5), the use of culturally loaded terms like ‘city’ and stonework ‘overlain with metal’, which imply a highly sophisticated technology.

Ultimately, I believe these problems of the Atlantis story can be resolved; its historical context, the location and identity of the peoples involved can be established with reasonable certainty.

Ancient World Views

Any ancient misconceptions of the island’s location would have been brought about by navigational methods developed within the Mediterranean Sea being applied by the first sailors to venture into the Atlantic Ocean. The mistranslation of numbers–particularly large numbers–gave rise to an unrealistic time-frame for the events described; for incredibly large distances and areas; and inordinate numbers of combatants involved in the war.

It should be understood that any descriptions and stories of foreign lands carried back to the Eastern Mediterranean, would have been based on the general impressions of the sailors and traders who interacted with the local inhabitants–probably with some language difficulties. In the hands of scribes who were literate, well educated but with no first-hand knowledge of the far west, these descriptions could have taken on a grandeur and scale commensurate with a more sophisticated world view. Plato’s descriptions in the dialogue would have added yet another layer of this kind of distortion. Many clues, when viewed in this light, can allow us to think in more realistic terms about the nature of the island and its people. If we accept a certain looseness in the interpretations of several aspects of Plato’s descriptions, Atlantis can fit very comfortably with a Neolithic to Bronze Age Britain. Archaeological evidence is, of course, the most important requirement needed to support a hypothesis such as this; but how can we get anywhere near an acceptable explanation for all or any points of contention, particularly at the western end of the equation?

Location

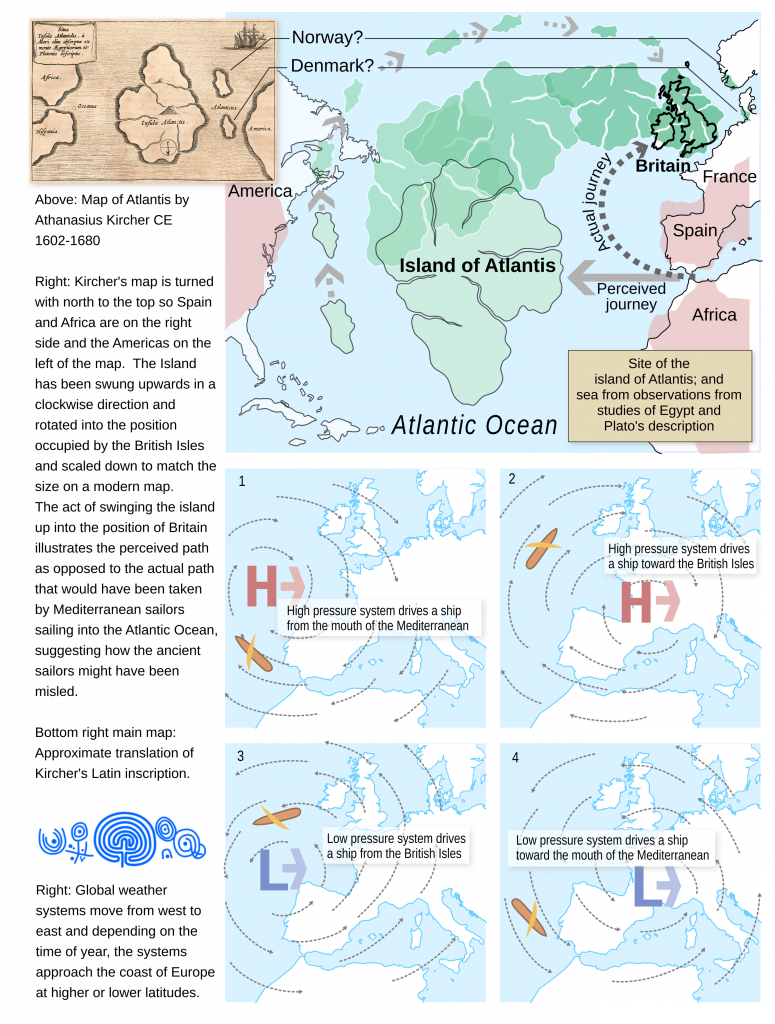

The starting point for my re-examination of the Atlantis story was triggered by Athanasius Kircher’s famous map of Atlantis. Kircher was a Jesuit priest, CE 1602-1680, he was a remarkable German scholar, widely known and respected throughout Europe for his theories on all manner of natural phenomena. Although much of his work, in the light of present day knowledge may seem rather ridiculous, some was truly inspired. He strove to rediscover lost knowledge from ancient sources and was the first to realise Egyptian hieroglyphs were a form of written language and not just a series of esoteric symbols. His notion of direct symbolic meaning however, was shown by Wallis Budge to be incorrect.

The Map

Kirsher’s map carries in the top left hand corner an inscription in Latin; ‘Situs Insulae Atlantidis, a mari olim absorpte ex mente Aegyptiorum et Platonis descriptio‘ which roughly translates as the ‘Site of the Island of Atlantis, that was swallowed by the sea, according to the minds of the Egyptians and Plato’s description’. It is rumoured that Kircher, whilst working in the Vatican Library, found the original map that was stolen from Egypt and taken to Italy by the Romans in the first century CE but none of this can be confirmed one way or the other because there is not a single trace of this ‘original’ map. Conspiracy theorists have suggested it has been deliberately hidden away in the Vatican library as “dangerous knowledge”.

The island in the middle of an up-side-down map of the Atlantic Ocean has been construed by some as South America or even Antarctica, both of which create extreme geographical and logistical problems for staging a war at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea. To me it looks much more like an over-sized Britain without the Irish Sea drawn in, and this fits much better what is known about the prehistory of the Mediterranean and Europe. The question is why would this island be shaped like the British Isles? There seems to be three possibilities: Kirsher either knowingly or even unconsciously used Britain as a model for his island; or, any similarity between Atlantis and Britain was entirely coincidental; or he had a source he believed to be an authentic representation of the island of Atlantis. The truth may never be known.

Since the time of Ptolemy, maps drawn by Europeans generally have north to the top since navigation was oriented to the north star, but not everyone agreed with this strategy. Hans Barnard in Maps and Mapmaking in Ancient Egypt states ‘[l]ikewise, our convention of having North at the top of a map would not have been understood in Ancient Egypt as this would have the water of the Nile flowing up.‘ My feeling is that the sun, being to the south of Egypt for most of the year and pretty much over-head during summer, it makes sense for any geographical reference to be oriented to the sun, the source of life itself. This seems to be borne out by the fact that the early maps and portolans of the Islamic world were mostly drawn with north to the bottom; i.e., the sun to the top. The famous clay world map from Babylon c 500 BCE was likewise drawn with north to the bottom.

Navigation

When Kircher’s map is turned with north to the top so Spain and Africa are on the right side and the Americas on the left of the Atlantic, and if the Island is swung upwards and rotated into the position occupied by the British Isles, it matches remarkably well, except Kircher’s island is about three times taller and three times wider than Britain; a discrepancy that will be discussed further. The act of swinging the island up into the position of Britain suggested how the ancient sailors might have been misled. At this point I must confess to many years having to draw the weather map for a daily newspaper, albeit in the southern hemisphere.

It was not until the 18th and 19th centuries in the modern era that meteorology made it possible to understand how weather systems and oceanic wave patterns work and to see how a navigational error could have been made in ancient times before the advent of celestial navigation.

To get some sense of the context of events in Plato’s story, it is necessary to go back to the sixth millennium BCE; to the Neolithic farming revolution that was characterised by the ‘Cardium and Impressed Ware’ of the maritime migrations in the Mediterranean, and the ‘Linear Banded ware’ (LBK) associated with the westward spread across the European continent to the Atlantic coast. This period of restless expansion within the Mediterranean resulted in the enclave settlements of southern France and Iberia which were established as early as the late fifth millennium. Influences from the Mediterranean spread north-westward to the Bay of Biscay; then to Brittany, and the Irish Sea region by c 4300/4200 BCE (Sherridan 2013); about 300 years before the arrival of the land-based Neolithic migrations from Continental Europe. In the context of Plato’s story, it would have been the maritime culture that carried the cult of Poseidon to Britain/Atlantis.

The first sailors to venture into the Atlantic Ocean from the Mediterranean Sea would have had an extensive set of navigational tools and tricks at their disposal that we can only guess at, but we do know from many ancient stories and legends that travellers routinely waited for the wind to blow them in a given direction to a particular destination; and this would have served them well enough in a familiar environment, but sailing with the wind in the Atlantic would result in a very strange outcome.

Understanding the weather systems of the North Atlantic Ocean and Europe is the key to knowing how early navigators might have been deceived about their direction of travel. The winds of a high pressure system approaching the Atlantic coast of Europe would be blowing in a clockwise direction. The wind and wave-following sailors of the Mediterranean would have been carried out from the Pillars of Hercules in a clockwise arc. A ship driven by these winds and maintaining a heading relative to the wind and waves would, over about a week, be driven northward and then to the north-east, towards Britain. The only visible sign that they were subtly changing direction would be that the sun appeared to rise and set in a different place each day. As the ancient sailors approached the west coast of Ireland—thinking that they had sailed directly out from the Pillars of Hercules—there must have been some confusion over the behaviour of the sun, but this could be attributed to the capricious and unknowable nature of the gods; and were unaware they were not travelling directly westward. A low pressure system would serve to carry them back home in an anti-clockwise direction.

So why would people sail boldly out into uncharted, unfamiliar waters? The idea that the Earth was surrounded by the “Ocean’s Stream” might have implied and inevitable re-connection with the encircled Earth. Alternatively, the answer might lie in the fact that all people of the Mediterranean and Middle East would only have known about bodies of water surrounded by land. Even traders in the Indian Ocean would have perceived the waters to be land-bound by Africa, Arabia and the Sub-continent.

There has been a long-standing belief among modern scholars that these ancient seamen restricted their sea-going habits to following coastlines. If this were true, sea-crossings from Africa to Europe would not have occurred, Malta would not have been settled, and artefacts from the south-eastern Mediterranean might not have reached the enclave settlements of southern France and Spain. An article published in the mass media in September 1997, spoke about the work of marine archaeologist, Dr Robert Ballard who said the most recent evidence of his study indicated ancient traders tended to sail point to point across open water rather than following coastlines.

I think here we have some credible answers to the problems relating to the whereabouts of this elusive island which was never really lost, but just misplaced. The problem of it being sunk beneath the waves can be rationally explained by looking at later sailors–namely the Pheonicians–using celestial navigation who would have sailed true west, not finding the Island and assumed it had sunk beneath the waves. Other possibilities will be examined in a more appropriate discussion.

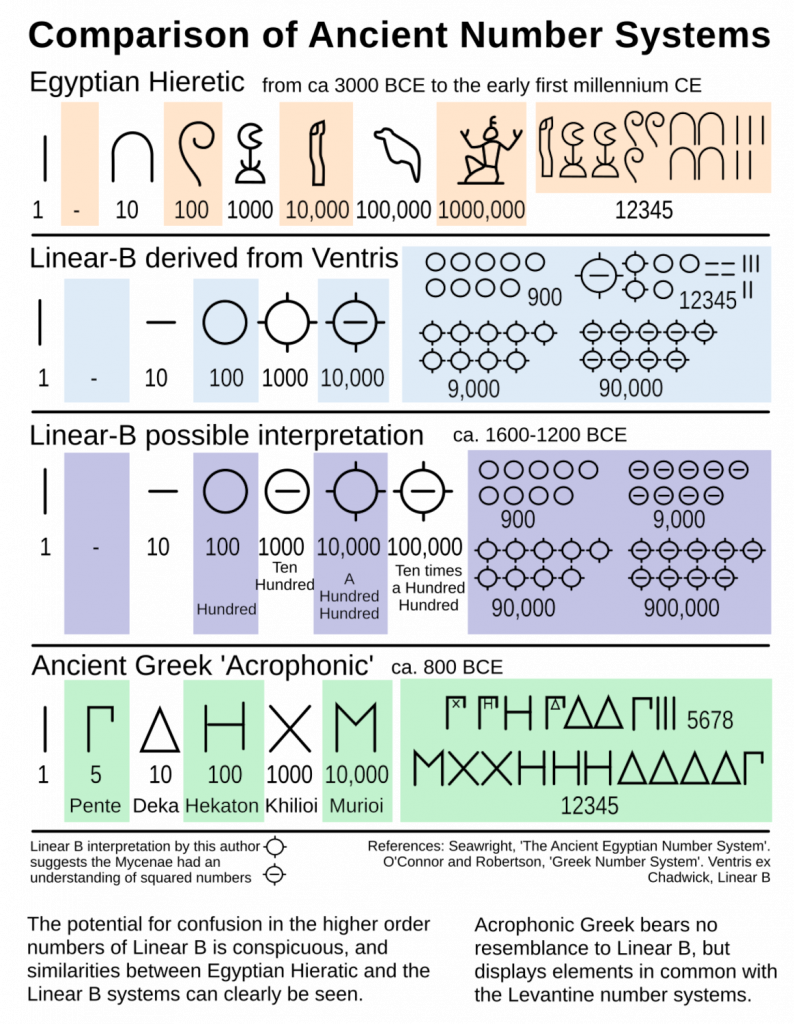

Large Numbers:- Linear B

The idea of mistranslation of numbers has not found general acceptance within the academic community, on the grounds that the numbering systems involved do not lend themselves to such mistakes. This certainly is the case when considering the Egyptian hieroglyphic numbers, and the classical Greek system involving the use of letters of their newly formed alphabet in their numbering system. But the most likely source for the kind of error we are looking for can surely be found in the numbers of the Mycenaean Linear B script of the Late Bronze Age, only a few hundred years before the time of Homer and Hesiod.

The problems of time and scale can be looked at together, because they are both plagued by inordinately large numbers and this would imply errors in translation; but only large numbers are affected. In the numbering system of Linear B, units up to ten were represented by single vertical strokes similar to our number one. Tens were expressed as horizontal dashes. One hundred was represented by a circle; ten hundred, by a circle with a horizontal dash set inside the circle; and a hundred-hundred was represented by a circle with four radial ticks around the perimeter. The use of the circle to express hundreds, and what we refer to as thousands (ten hundred) and tens of thousands, (hundred hundreds) must be the most likely source of an error of translation. Of all the numbers presented in Plato’s descriptions, only the large numbers involving circles with various small marks that cause problems of disbelief, and when divided by a factor of ten they all seem quite credible. It should also be considered that both Linear A and Linear B number systems functioned in a similar manner to that of Egypt.

Time

If we accept this error of translation, instead of the 8 or 9 thousand years stated by the old Egyptian priest, we can go back 900 years plus about 120 unrecorded, years to the beginning of the New Kingdom c 1570 BCE; then we can add just 50 years to take us back to 1620 BCE, near to when the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini) erupted around the end of the Middle Bronze Age. It’s widely accepted that this is the catastrophe that brought an end to hostilities between Athens and Atlantis spoken of in Solon’s conversation with the Egyptian priest.

In the Critias, the priest says ‘in all nine thousand years have elapsed since the declaration of war between those who lived outside and all those who lived inside the Pillars of Hercules.’ And yet, in the Timaeus the priest tells Solon that their respective institutions—Egyptian and Greek—are 8000 and 9000 years old [corrected to 800 and 900 years]. This has been seen as an error or confusion on Plato’s part, having the same time frame for the establishment of the Greek culture and the beginning of hostilities with Atlantis. This is not the contradiction it may seem. If Athens was a newly established Minoan or Cycladic colony on the Greek mainland, during the Early to Middle Bronze Age for instance, there would be little room for criticism on this point. It could simply mean the distinction between the Athenians, and the Greek people in general was not clearly dealt with and could further imply the hostilities may have been the result of an Aegean incursion onto the mainland.

Dimensions

Critias’ description of Atlas’ ‘city’ and its environs very clearly demonstrates problems the author had with large numbers, and yet small numbers present no problem at all with regard to scale and distance which were given in ‘stades’ (200 yards or approx. 184 metres). Critias described the situation of Poseidon’s residence as ‘the most beautiful and fertile of all plains, and near the middle of this plain about fifty stades (10,000 yards) inland a hill of no great size’. Three rings of water were placed by Poseidon around the hill, the largest of which was 23 stades (2.6 miles/4km) in diameter. ‘Beyond the three outer harbours there was a wall, beginning at the sea and running right round in a circle, at a uniform distance of 50 stades [10 000 yards, 5.7 miles/9.5km] from the largest ring and harbour and returning on itself at the mouth of the canal to the sea’. Although the description of the earthworks and the bounding wall is somewhat surprising in scale, none of these measurements exceed the bounds of credibility. The story is quite different for the description of the surrounding plain due to the introduction of numbers larger than a hundred.

The city was surrounded by a uniformly flat plain, which was in turn enclosed by mountains which came right down to the sea. This plain was rectangular, measuring 3000 stades (341 miles/568km) in length and at its midpoint 2000 stades (227 miles/378km) in breadth from the coast. These figures are of course unacceptably large as it would be impossible to see with the naked eye—due to the curvature of the earth—that such a vast plain was surrounded by mountains.

Critias himself expresses disbelief at the measurements pertaining to the plain and its ditches but says, ‘I must give them as I heard them’. However, if we consider the very likely confusion between hundreds and thousands—as seems to have been the case with the chronology—we have a far more likely set of figures. By converting the number of stades from thousands to hundreds, we end up with a plain 300 stades (approx. 34 miles/57km) by 200 stades (22.7 miles/37km). This new scheme can now fit quite comfortably in several places around the coast of Britain. The eastern coast of the Irish Sea is of particular interest in Plato’s reference to the plain being ‘at the centre of the island near the sea’, which seems to suggest the plain was situated on an intrusion or gulf, such as the Irish Sea. This idea makes sense if there was a land-bridge of glacial debris connecting north-eastern Ireland to the west coast of Scotland.

Military

The Benjamin Jowett translation gives an inventory of Atlas’ city’s contribution to the war effort against Athens based on 60,000 allotments with an extraordinarily large army of 720,000 military men, 10,000 chariots with charioteers and combatants, 40,000 horses and 1200 ships. If we divide these numbers by ten we end up with what is still a huge number, but moving in the direction of credibility: 72,000 military men, 1000 chariots, 4000 horses and 120 ships.

Desmond Lee‘s account is slightly different. Still with 60,000 allotments but with a massive army of 10,800,00 military men, 10,000 chariots with charioteers and combatants, 40,000 horses and 1200 ships. If we divide these numbers by ten we end up with a slightly less incredible number: 1,800,000 military men, 1000 chariots, 4000 horses and 120 ships.

The discrepancy between these two translations, where Lee gives an allotment area of 10 square stades and Jowett gives the area as 10 stades square, i.e. 100 square stades, is an ideal example of just how easily errors of translation can be made.

One Island

If we try to fit Great Britain into the role of Plato’s single large island, the rather obvious separation of Ireland from the rest of Britain causes a problem. It’s well known that Ireland has been moving away from England for millions of years with an ever widening rift valley separating the two islands. But, given that the Drumlins of Ireland are essentially glacial moraines from the Scottish Highlands, logic would have to allow for a temporary land bridge of glacial debris between Ireland and southern Scotland which could have remained, perhaps down to the fourth or even third millennium, until the sea level rose high enough for the waters of the Atlantic and the Irish Sea to come together to start the process of rapid tidal scouring, which would eventually clear much of the Ice Age debris from the channel.

Five Sets of Twins

The creation of Atlantis in geopolitical terms according to Plato begins with Poseidon’s arrival on the island where he encounters the ‘original earth-born inhabitant’ named Evenor, with his wife Leucippe and their daughter, Cleito. Poseidon was attracted to Cleito and had intercourse with her and the union between Cleito and Poseidon produced five sets of male twins. The first of these were; Atlas who was given his mother’s home district and the land surrounding it–the biggest and best allocation–and made him King over the others; and his twin brother Eumelus who in his own language was called Gadirus, and he was given dominion over the ‘furthest part of the island towards the Pillars of Heracles and facing the district now called Gadira’. Gedes or Cadira on the Atlantic south coast of Spain, just outside the Strait of Gibraltar is universally identified as the ancient Gadira. This logically implies that Eumelus was given control over what is now Ireland and Atlas had dominion over what is now the main island; England, Cornwall, Wales and Scotland.

As I understand it, Poseidon was a Mediterranean god of the sea whose religion was carried westward by Neolithic migrants or traders who reached Britain c 3300 BCE via the Atlantic Ocean or from the Gulf of Lion in southern France to Brittany and then to the Irish Sea. Under the premise that the early Mediterranean sailors were deceived into thinking that Atlantis was opposite the Pillars of Hercules, the western coastline of Ireland would indeed have been facing Cadiz; therefore, it would be perfectly reasonable to equate Ireland with the ‘furthest part of the island’ nearest to the ‘district now called Gadira’.

The others twins Poseidon made ‘governors, each of a populous and large territory’… The second pair of twins were Ampheres and Euaemon; the third pair were called Mneseus and Autochthon; the fourth were Elasippus and Mestor; and the fifth pair were Azaes and Diaprepes.

According to Irish legends, there were five ancient provinces of Ireland and it is an odds-on bet that there were also originally five provinces on the British mainland before the arrival of the Iron Age peoples from the continent. Given the probability that the two islands were once joined by a land-bridge formed by glacial debris, this description makes perfect sense with each part of the island being divided into five provinces. Hence, we have five sets of twins: The five trilithons that were added to Stonehenge, about 2000 BCE, may also reflect in a symbolic way, the five sets of twins or the 10 provinces of Britain.

‘The eldest, the King, he gave a name from which the whole island and the surrounding ocean took their designation of ‘Atlantic’, deriving it from Atlas the first King…’ It is interesting however, that Poseidon’s first-born son has the name of a Titan who had his origin in eastern Europe, Caucasia or somewhere around the Black Sea. This to my mind suggests the second wave of Neolithic people to arrive in Britain were from the Pontic/Aegean region via the Danube valley and central Europe who did so a couple of hundred years after the Mediterranean migrants, and it was probably these people who carried the Titan cult to Britain. The Continental farmers–possibly the Linear Banded culture–having arrived later, would possibly have been adopted into the British family, so to speak, as ‘children’ of the earlier culture, but they may have been dominant enough to hold the rank of senior son.

In reflecting on the similarities between Atlantis and Britain of the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age when the wealth and prestige, and the vast sacred spaces surrounding Stone Henge, it’s difficult to dismiss Plato’s assertion that ‘[t]hey and their descendants for many generations governed their own territories and many other islands in the ocean…‘ and ‘Atlas had a long and distinguished line of descendants, eldest son succeeding eldest son and maintaining the succession unbroken for many generations; their wealth was greater than that possessed by any previous dynasty of kings…‘

There are so many other ancient myths and legends that seem to feed into the story of Atlantis, starting with Atlas being banished to the far west, the story of Prometheus–brother of Atlas–stealing the metal-working fire of the Gods and giving it to his brother Titans to the north. The story of Perseus, a prince from an Aegean island journeying to Hyperborea to cut off the head of Medusa, a daughter of Atlas; and the 11th labour of Hercules to retrieve the sacred apples of Hera from the Hebrides where Atlas lived.

These stories and their connection to Atlantis will be discussed in more detail later.

A Logical Problem

There is a problem in connecting an event that occurred on a ‘single day and night’ in regions so far separated from each other as Greece, and an island in the Atlantic Ocean.

When Plato tells of this cataclysmic event when the fighting men of Athens ‘were swallowed by the earth‘ and the fighting men of Atlantis were ‘swallowed up by the sea‘ and the whole island of Atlantis vanished on the very same day and night in the very same catastrophe; it’s difficult to understand how this could have been perceived in ancient times. Maybe the synchronism of these events could have been dictated by the gods, but it’s more likely that this is where different sources might have create a logical conflict. Perhaps it would have been more realistic for Plato to have suggested the fighting men of Atlantis who were waging war against Athens—from the southern coast of the Peloponnese peninsula—were swallowed by the sea. This could certainly have been the case, because the southern coast of the Peloponnese would have been exposed to the full force of a massive tidal wave generated by an earthquake in the region of the Thera. Athens, on the other hand would have been shielded from the direct force of a tsunami by the intervening Cycladic islands, but it certainly did suffer extreme land-slides and the liquifaction of the slopes of the Acropolis as is evidenced by geological core samples taken at Piraeus, the port of Athens. In modern times we have seen the terrible devastation and loss of life brought about by such events.

Loaded Terms

It can easily be imagined how a large settlement may in some people’s language be referred to as a ‘city’. And stones simply burnished with soft metal ores could well be said to be ‘overlain with metal’. The Interpretation of any terminology Plato might have found in his sources referring to architecture and other features in the far west would have been influenced by his own worldview.

The Parthenon and other temples of the Acropolis for instance would certainly have served as models for the temple devoted to Poseidon, who was after all, related to Zeus and Athena. Plato may have assumed the Atlantean city would match the grand architecture of his Athens, perhaps not realising remote societies were markedly less sophisticated than his own. Peoples of the north had made extraordinary leaps in technology, science and innovation which gave rise to many wonderful dynamic artefacts but not with the same level of refinement as in the East.

Given the above considerations, I think we can dispense with these kinds of interpretive terminologies as a bar to getting at the elementary truth.

Who’s Who:- Ethnicity and Ideology

There can be little doubt that the coming together of at least two very divergent world views would be the source of extreme and prolonged conflict. On one hand we have the fairly sparsely populated egalitarian groups of temperate to sub-polar Eurasia and Europe; and on the other, we have the large populations of the tropical and sub-tropical Mediterranean and Middle-east; each with their different life ways. So I think it is appropriate to draw a more or less distinct line between the cultures of the East and South, and those of the North and West.

East and South

By identifying the goddess Athena with Neith, the goddess of Sais in Egypt, Plato adds weight to the idea that Athena was introduced from the east to both regions. This in turn would imply the priest regarded Egyptians to be in a way kindred to the Aegean cultures, including Athens, and it would have been these peoples the Egyptians understood to be the ‘Greeks’: Hence, Solon would have been treated as an honoured guest on his visit to Egypt.

The Minoan Palace Period is arguably one of the best known cultural periods of the region, which effectively came to an end when the whole area was devastated by earthquake and the eruption of Thera c1620 BCE. Unfortunately, not much is known about the Athens region during this period, but if what Plato wrote; that there were ‘earthquakes and floods of extraordinary violence; and in a single dreadful day and night all your [Athens’] fighting men were swallowed up by the earth’ this would make perfect sense of the lack of archaeological evidence for Middle Bronze Age occupation. If traces of eastern architecture in the area prior to the eruption c 1620 BCE. could be found in the coastal region of the Athenian plain, this would account for Plato’s description of the catastrophic annihilation of Athens prior to the Mycenaean developments of the Late Bronze Age.

North and West

Neolithic traders and farmers–signified by their impresso and cardial pottery–from the East during the 7th millennium via the Mediterranean Sea–reached the far west c 5400 BCE, and on to the British Isles by the late 5th to early 4th Millennium. The origin of these people is not entirely clear but I suspect they came from the western edge of the Black Sea and northern Aegean region of Thrace. There is good reason to suggest it was these people who carried the cult of Poseidon to the far West. Since Poseidon is also known as the “father of horses”, this places him in or around the Pontic region where horses were first domesticated. So it makes sense that the Impresso and Cardial pottery might be seen as the footprint of Poseidon and the beginning of the Atlantis story.

(There will be a further, in-depth discussion on this topic).

The continental Neolithic farmers from the Balkan Peninsula reached the British Isles around the middle of the 4th millennium via the Danube valley and the Northern Plains. These people who, intermixed with the northern Hunter-gatherers were representative of the tall shamanistic peoples of the north who I believe were thought of in Greek legend as the Titans of whom, Atlas, a senior titan was ‘banished to the far west’ after being defeated by the gods of Olympus.

It was a mix of farmers and traders, along with various indigenous groups needing to find some way of getting along that necessitated the establishment of the 10 provinces ruled by five sets of twins; thus establishing peaceful settlements in Atlantis/England and Ireland.

The Amesbury Archer who arrived in Britain from the upper Rhine region lived between about 2,500 and 2,300 years BCE is thought to have been associated with the first megalithic construction of Stone Henge. It’s worth considering that the trilithons consist of five sets of twin upright stones connected by a lintel; ergo, five sets of twins. Under this hypothesis, it was these people who constituted the godly Atlanteans who were later ‘corrupted by men of the world’.

By the middle of the 3rd millennium the Beaker Burial phenomenon arose with the Iberian Maritime Beakers, and Central and Northern Europe, the Bell and Funnel Beakers displaying extensive trade networks across Central Europe, Britain and even onto Northwest Africa.

Meanwhile

In the east, north of the Black Sea, from the early 4th mill. BCE, amid conflict and animus there arose a Warrior Class, even before the introduction of Bronze. The ingenuity and innovation that occurred, along with the domestication of the horse and the invention of the wheel gave rise to powerful changes that meant the world would never be the same again. From the early 3rd millennium the Corded Ware, Globular and Kurgan cultures arose spreading their war-like attributes as far west as Germany, Italy and Spain, giving rise to the prominent Unetice and Al-Argave cultures. I submit that it was these people who were referred to by Plato as the corruptors of the Atlantean Beaker folk of Britain.

The degeneration referred to by Plato could very well be explained by the extended power of the Warrior Elites across Europe to Britain. However, it can be observed that the sacred landscapes of Britain retained a certain amount of influence across Europe, even further than the Tyrhennian Sea as Plato stated.

The EBA of Europe was contemporary with, and had very similar levels of technology to the Aegean Middle Bronze Age and this suggests it was a leap-frog (Neolithic to Bronze) technology that was ushered into Greece by peoples from the north and west. Prior to, and during this period (c 2050 – 1680 BCE) there was a great deal of movement and activity across northern Europe from the Pontic Steppe to the Atlantic Ocean. From here I believe we move into the Balkan/Aegean realm of conflict referred to by Plato in the T&C dialogues.

Points worth considering

We can probably never be sure of arriving at the absolute truth in the Atlantis debate but there exists a great deal we know about the past that can add weight to a more or less satisfactory resolution; and these are as follow:

Certain aspects of the field systems, circles and henges of Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain could credibly apply Plato’s descriptions based on early reports taken back to the East.

If a Neolithic to Bronze Age site closely matching Plato’s description exists it might be either hidden beneath the coastal waters of the Irish Sea or below peat-bogs, moors or swamps that have formed since that time, or perhaps parts of it have already been discovered, but not recognised as such, because of the lack of a sufficiently broad overview.

Suggestive evidence of contact between Britain and Greece is in the form of what looks like a Mycenaean dagger engraved into one of the trilithon stones of Stonehenge and there is similar evidence in at least one of the Bronze Age barrows close by.

Artefactual evidence of links between Beaker Burial folk of Wessex and Mycenae more than 2000km away shows an abundance of just such evidence in the early grave-circles at Mycenae. Amber necklaces and other jewellery of Wessex manufacture, Bronze rapiers with tongue-grip hilts often depicted on the “battle scene” ring seals of Mycenae are among the earliest swords known, and are very similar to those found as far away as Britain and Ireland.

The presence of material goods, which could have been traded, hand to hand over such distances does not prove the presence of people, but equally, it does allow for the possibility of personal travel, perhaps in fairly large numbers. Travel from one end of Europe to the other would require only about three months and any such passage could have been well assisted, particularly if the island was revered as a kind of holy-land (an idea that’s gaining weight in recent times). If Britain was regarded throughout Continental Europe as a sacred land, this would explain why the inhabitants of an island so far away in the Atlantic Ocean would have held such a prominent position in the story told by Plato when he said ‘the Atlanteans held sway over Europe to the Tyrhennean Sea’.

Ancient understanding of the world’s geography would have varied throughout time so it’s almost impossible to know exactly how Europe was perceived by Aegean people prior to the time of Plato; but it can be assumed that Europe extended from the Black Sea to the Atlantic which was highly connected in trade and influence.

The only indisputable proof that people from as far away as the British Isles would have to lie in genetic links between the earliest rulers of Mycenae and the elites of Wessex. Even so, the involvement of different peoples across Europe–as implied by Plato–could make for a very confused picture. The present day Peloponnesian male population is comprised of around 20% (one in five men) R1b which is the main component of Atlantic Europe which originated on the Pontic steppe. This overly simplified notion is in keeping with the Bronze Age events from the Black Sea to the Atlantic along with the ancient stories of Atlas being banished to the far west after the Titans were vanquished in the war with the Gods.

Apollodorus, a second century Greek scholar of Alexandria, in The Library of Greek Mythology, has Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and Menelaus his brother, king of Sparta, as descendants of Alcyone—one of the Pleiades—a daughter of Atlas, and this seems a direct legendary confirmation of an Atlantis-Mycenae connection. Apart from references to Atlas in Greek Laconia, other references have both Perseus and Hercules meeting him during their excursions to the far west. And as Plato tells us, both the island and the Atlantic Ocean were named for Atlas.

In short, the rulers of Mycenae and their associated groups might have been the descendants of the British/Atlantean and European survivors of Plato’s devastation of the region, which can reasonably be associated with the earthquakes and eruption of Thera, c 1620 BCE.

Note:

This has been a brief overview of my hypothesis. The main points referred to above will be treated in more detail in a separate, more focused way and it is in these offerings that credits and references will be given in bibliographies pertinent to each subject.