What Plato Wrote

Introduction

Plato’s dialogues, Timaeus and Critias (T&C hereafter) have been the subject of extraordinary amounts of debate and conjecture about the veracity or otherwise of the story presented by Critias. In modern times, we have the doubts and scepticism of some Classical scholars, who claim that Plato only used the Atlantis story as an allegory and morality tale involving the exemplary community of ancient Athens and their battle against the the once ‘godly’ people of Atlantis after their fall from grace due to contact with men of the earth. Other scholars have suggested there is some truth to some degree in the story and have posited various scenarios usually confined to sites within the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas for the location of the island; perhaps this is because of a difficulty in accepting the mobility of ancient people over large distances. But modern research shows that there was a great deal of movements over vast distances in ancient times. On the other hand, the story has been unquestioningly embraced by those who wish to live in a world where fantasy and dreams of a Utopia rising up from the past—usually from somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean—can create a bright new future. This is of course far removed from reality, and is far from benign in its influence, because it is fraught with the dangers of delusion and falsehood.

Almost certainly, Plato would have put a kind of morality spin on the story, but there is no good reason to doubt that he used what he understood to have been actual historical events to demonstrate the virtues of a decent society. It should be noted that he insisted at least seven times that the story of the war between Athens and the Atlanteans was a true one. And in other works he seems careful to ensure his words are understood in the right way.

As a member of the privileged Athenian family, he must have had extensive resources at his disposal. Plato has been referred to as the great synthesiser and in all likelihood he used this capacity to verify and expand on the story told by Critias; after all there was a vast narrative background of oral and written traditions that are relevant to this story that needed to be taken into account.

The following is an analysis of what Plato actually wrote, drawn from the translations of Benjamin Jowett (1817 – 1893), with occasional cross-referencing of Desmond Lee’s translation for the Penguin Classics series published in 1965. It is aimed at explaining how ancient dialogues might relate to a modern understanding of the ancient world and how misconceptions and mistranslation from ancient times have muddied the waters and limited our ability to accept the story as factual.

The case for the veracity of Plato’s T&C dialogues is supported to a large degree by the art and other artefacts found in the Grave Circles at Mycenae and other burial sites from the Mycenaean period. We should assume that most artwork of ancient times was always purposeful and usually narrative in nature; or at least referential to a narrative. Several images of Mycenaean artistry will be included to support the present hypothesis.

The story Critias tells was thought to have been brought to Greece around 600 BCE by Solon, a statesman said to have visited Neith–a district of Sais in Egypt–during the reign of ‘King Amasis’ who almost certainly was the reigning Pharaoh Ahmose towards the end of the Saitic period not long before the Persians established a foothold in Egypt, in 525 BCE. The priest with whom Solon spoke claimed a relationship between Egypt and Athens through the goddess Athena/Neith which implies a common early influence in the establishment of both Egypt and the Aegean cultures. General consensus has it that the cult of Athena was introduced to the Greek mainland from Asia Minor or the Levant, perhaps during the late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age.

An old priest told Solon there was a time, “before the great deluge, when the city which now is Athens was first in war and in every way the best governed of all cities, is said to have performed the noblest deeds and to have had the fairest constitution of any of which tradition tells, under the face of heaven.“ The priest went on to tell Solon that Athena founded the city of Athens “a thousand years before ours, receiving from the Earth and Hephaestus the seed of your race, and afterwards she founded ours [Neith], of which the constitution is recorded in our sacred registers to be eight thousand years old“ [all up, nine thousand years prior to Solon’s visit].

The eight and nine thousand years time span before the time of Solon would take us back to the very earliest known phases of settled communities. Even the earliest level of Jericho is dated to the early eighth millennium BCE; James Mellaart, (1976) has the Neolithic in Anatolia at Catal Huyuk dating to about 6500 BCE. The Natufian Origins of Agriculture following the Younger Dryas (ca. 11,000 to 10,300 B.P.) is regarded as the earliest manifestation of the ‘‘Neolithic Revolution’’. In the Levant it is known as the Khiamian, perhaps dating from as early as 10,500 B.P. [ca 8500 BCE] (Bar Yosef, 1998). Aurenche and Kozlowski (1999) have the Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic in the Amuq valley and Cilicia where the northern Levant meets Anatolia somewhere between 9200 and 8000 BCE. There are no known Neolithic settlements older than these.

This incongruity has always been one of the major obstacles to a sensible resolution of the Atlantis question. The extraordinary time-frame given by the priest, in combination with Plato’s description of a technology that belongs in part to his own era and certainly within the ages of metallurgy, is probably the main factor in the fantastic and false notion of an unknown super civilisation which has plagued the story in modern times and hindered its resolution.

Many writers on the subject hold the more realistic view that if the given number of years is divided by 10, a much more sensible picture emerges. In other words, if we go back 800 and 900 years before Solon’s visit to Egypt–less than 100 years after Amosis I liberated Egypt from the grip of the Hyksos rulers of the Second Intermediate Period–we end up with a date of about 1400 or 1500 bce. The records that Solon’s priest had access to would probably only have gone back to the time of Amosis I and the re-establishment of an Egyptian archive might have taken time to develop, leaving a short-fall in the number of years allotted to their chronology. If this were the case, an adjustment of two hundred years or so would set the end of the war and the catastrophic destruction at the time of the Thera eruption; which makes a lot more sense.

From Timaeus

The dialogues begin with Socrates addressing Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates recounting the previous day’s meeting and he asks them to reciprocate with their own contributions. The opening stages are devoted to Socrates outlining his views of an ideal society and how it should be governed. His vision of an orderly, well run society was of one divided into four classes—farmers, craftsmen, the military and an elite class of philosopher-statesmen who make decisions for the welfare of all. But Socrates bemoans the fact that his model society is motionless… He says, “I would be glad to hear some account of it engaging in transactions with other states“. In other words, he would like to see a working example of the ideal state and he challenges the three companions to furnish him with ideas of just such a society. Perhaps this aspect of the dialogue induces analysts and commentators to assume that the T&C dialogues are works of fiction, constructed purely for this reason.

Socrates introduces the speakers who will contribute their wisdom to the question of how an ideal society might be brought into existence:

Here is Timaeus, of Locris in Italy, a city which has admirable laws, and who is himself in wealth and rank the equal of any of his fellow-citizens; he has held the most important and honourable offices in his own state, and, as I believe, has scaled the heights of all philosophy;

…and here is Critias, whom every Athenian knows to be no novice in the matters of which we are speaking;

…and as to, Hermocrates, I am assured by many witnesses that his genius and education qualify him to take part in any speculation of the kind. And therefore yesterday when I saw that you wanted me to describe the formation of the State, I readily assented, being very well aware, that, if you only would, none were better qualified to carry the discussion further,

Timaeus’ contribution is in his vast knowledge of the nature of things. Critias is a statesmen with a story to tell. And it is widely held that Hermocrates was to have dealt with the subject on which Plato later Based the ‘Laws’ – the establishment and governance of a society. His part in the T&C dialogues did not take place for reasons that are not entirely clear. It’s possible Plato did not get to finish this particular work; perhaps because of interruptions; or perhaps it was more personal than is usually recognised. Plato is said to have been captured and held in Syracuse on Sicily which happened to be Hermocrates’ home town and it might be conjectured that Hermocrates was somehow involved in Plato’s imprisonment, creating bad feelings or resentment.

# Discussion Pending:-

Hermocrates reveals to Socrates that Critias has a story he might find suitable for the purpose of illustrating the ideal society. Critias begins by telling Socrates the story of Solon, the “wisest of the seven wise men“ who brought the story back from Egypt and vowed it was true. Critias then told Socrates of a tale which;-

though strange, is certainly true, having been attested by Solon, who was the wisest of the seven sages. He was a relative and a dear friend of my great-grandfather, Dropides, as he himself says in many passages of his poems; and he told the story to Critias, my grandfather, who remembered and repeated it to us.

Solon was a friend and relation of Dropides (Critias’ great grandfather), who told it to his son, Critias who was grandfather to our Critias of the dialogue who in turn seems to be Plato’s maternal uncle and became one of the thirty tyrants of Athens installed by the Locrians at the end of the Peloponnesian wars.

*The naming of a child after a grandparent was and still is a well held tradition in Greece and even throughout Europe.

# Discussion Pending:-

The old Egyptian priest’s story continues:-

There were of old, he said, great and marvellous actions of the Athenian city, which have passed into oblivion through lapse of time and the destruction of mankind, and one in particular, greater than all the rest. This we will now rehearse. It will be a fitting monument of our gratitude to you, and a hymn of praise true and worthy of the goddess, on this her day of festival.

The story relates to the achievements of Athens long ago prior to the ‘greatest destruction of all’. This, in all probability was the Minoan eruption of Thera. Although evidence exists for many floods and destructions in ancient times, as far as is know, none were more catastrophic and widespread than this.

Around 600 BCE Solon was said to have visited Neith in the district of Sais Egypt during the reign of ‘King Amasis’ who almost certainly was the Pharaoh Ahmose who reigned at the end of the Saitic period just before the Persians established a foothold in Egypt, in 525 BCE. The priest with whom Solon spoke claimed a relationship between Egypt and Athens through the goddess Athena/Neith which implies a common early influence in the establishment of both Egypt and the Aegean cultures. This might further suggest that the cult of Athena was introduced to the Greek mainland–possibly at or near Athens in Attica–from Asia Minor or the Levant, perhaps during the late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, creating conflict with the indigenous mainland Helladic peoples, thus giving Athena her warlike nature.

# Discussion Pending:-

The story goes:-

In the Egyptian Delta, at the head of which the river Nile divides, there is a certain district which is called the district of Sais, and the great city of the district is also called Sais, and is the city from which King Amasis came. The citizens have a deity for their foundress; she is called in the Egyptian tongue Neith, and is asserted by them to be the same whom the Hellenes call Athene; they are great lovers of the Athenians, and say that they are in some way related to them.

A very old priests told Solon:-

There have been, and will be again, many destructions of mankind arising out of many causes; the greatest have been brought about by the agencies of fire and water, and other lesser ones by innumerable other causes.

As for those genealogies of yours which you just now recounted to us, Solon, they are no better than the tales of children. In the first place you remember a single deluge only, but there were many previous ones;

…in the next place, you do not know that there formerly dwelt in your land the fairest and noblest race of men which ever lived, and that you and your whole city are descended from a small seed or remnant of them which survived. And this was unknown to you, because, for many generations, the survivors of that destruction died, leaving no written word. For there was a time, Solon, before the great deluge of all, when the city which now is Athens was first in war and in every way the best governed of all cities, is said to have performed the noblest deeds and to have had the fairest constitution of any of which tradition tells, under the face of heaven.

Prior to the catastrophic eruption of Thera, the Cycladic/Minoan culture dominated the region so it can logically be deduced that any city in the vicinity of Athens prior to the destruction would have been an Aegean city. The archaeological site of Kolonna on the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf between the Peloponnese and Attica tells the story of a series of destructions and sudden cultural changes prior to the Thera eruption. It was after this catastrophe that the Mycenaeans rose to dominance in and around the Aegean Sea.

# Discussion Pending:-

Solon asked about these former citizens. The priest replied, the goddess…

…founded your city a thousand years before ours, receiving from the Earth and Hephaestus the seed of your race, and afterwards she founded ours, of which the constitution is recorded in our sacred registers to be eight thousand years old. As touching your citizens of nine thousand years ago, I will briefly inform you of their laws and of their most famous action; the exact particulars of the whole we will hereafter go through at our leisure in the sacred registers themselves. If you compare these very laws with ours you will find that many of ours are the counterpart of yours as they were in the olden time.

The timing of these founding events–if divided by a factor of ten–are of extreme interest and will be discussed in conjunction with an argument and reasons for a mistranslation of large numbers. Aegean contact from the East, prior to that of Egypt is confirmed by archaeology, contrary to the popular notion that Egypt is the older culture.

# Refer:- Overview – Ancient Errors – Numbering systems and Linear-B

Athenian societal structure:-

In the first place, there is the caste of priests, which is separated from all the others; next, there are the artificers, who ply their several crafts by themselves and do not intermix; and also there is the class of shepherds and of hunters, as well as that of husbandmen; and you will observe, too, that the warriors in Egypt are distinct from all the other classes, and are commanded by the law to devote themselves solely to military pursuits;

…moreover, the weapons which they carry are shields and spears, a style of equipment which the goddess taught of Asiatics first to us, as in your part of the world first to you.

Here is a critically important point to the story which helps identify just who the Athenians were and from whence they came – the use of shields and spears as a style of warfare in ancient near-eastern societies is well documented in ancient artwork and archaeology and this is distinctly different from the suite of weapons introduced into the Balkan region by the Proto-Mycenaeans.

# Discussion Pending:-

In Timaeus, Critias gives a brief account of the Atlanteans;-

This power came forth out of the Atlantic Ocean, for in those days the Atlantic was navigable; and there was an island situated in front of the straits which are by you called the Pillars of Heracles; the island was larger than Libya and Asia put together, and was the way to other islands, and from these you might pass to the whole of the opposite continent which surrounded the true ocean; for this sea which is within the Straits of Heracles is only a harbour, having a narrow entrance, but that other is a real sea, and the surrounding land may be most truly called a boundless continent.

One of the major stumbling blocks to resolving our understanding of the story as a whole is this particular problem. How can the island have been in front of or directly opposite the Pillars of Hercules? The answer lies, I think, in the navigational practice of following the wind as it was developed in the Mediterranean basins and wrongfully applied to conditions in the Atlantic Ocean.

The knowledge that the Middle Sea was ‘only a harbour’ when compared to the Atlantic Ocean argues for a well established geographical knowledge of the ancient world around the Mediterranean Sea and Europe. The size of the island will be discussed below.

# Refer:– Overview – Ancient Errors

Geographical location and influence:-

Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent, and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia. This vast power, gathered into one, endeavoured to subdue at a blow our country and yours and the whole of the region within the straits; and then, Solon, your country shone forth, in the excellence of her virtue and strength, among all mankind.

The realm and sphere of influence as described, matches extremely well, the distribution and influence of the Beaker cultures of Western Europe even to the point of inhabiting the north-western coast of Africa (Libya). At this time, various groups north of the Black Sea, dominated by warrior elites of groups such as the Corded Ware and Yamnaya cultures expanded westward with their domesticated horses, wheeled vehicles and devastating new bronze weapons creating extensive trade networks across Eurasia.

An idea of Europe being “gathered into one” might be seen as a violent expansion from the north, or perhaps crusade against the incursion into the European realm by eastern people via the Aegean Sea. Perhaps it was a war of ideology and religion; an animistic religion of a tribal or clan-like structure versus the religion of gods, kings and large highly structured, kleptocratic societies. Given the conflicts between societies of the Fertile Crescent and those of the Caucasians and Pontic regions, aka; the war between the Titans and the Gods, this looks very much like a continuation of an old enmity.

# Discussion Pending:-

Athens, friends or foes:-

She was pre-eminent in courage and military skill, and was the leader of the Hellenes. And when the rest fell off from her, being compelled to stand alone, after having undergone the very extremity of danger, she defeated and triumphed over the invaders, and preserved from slavery those who were not yet subjugated, and generously liberated all the rest of us who dwell within the pillars.

The fact that the Athenians were forced to ‘stand alone’ in the battle against Atlantis suggests that allegiances were fragile and mixed as has been the case in almost all wars recorded throughout history.

Disaster:-

But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

The ‘Minoan’ eruption of Thera eruption in the late 17th century BCE is widely accepted as the event Plato refers to in the T&C dialogues and the description he provided would certainly be commensurate with such an event. There is much to be said on the destruction of Athens and the more knotty problem of the sinking of the island and the impenetrable barrier to the Atlantic Ocean; these topics will be dealt with more or less separately.

The next day Critias explains the order of their entertainment for Socrates.

From Critias

Time-scale, size and location

After the introductory speeches and good natured banter between the four characters Critias launches into his discourse as follows:-

Let me begin by observing first of all, that nine thousand was the sum of years which had elapsed since the war which was said to have taken place between those who dwelt outside the Pillars of Heracles and all who dwelt within them; this war I am going to describe.

The time-frame of eight and nine thousand years before the time of Solon’s alleged visit to Egypt c 600 BCE is completely irreconcilable with archaeological evidence. A more realistic picture emerges if the incredibly large numbers are divided by ten which takes us back to about 1500 BCE. In Egypt about this time, the Hyksos rulers of the Second Intermediate Period were evicted by Ahmose I who established the 18th Dynasty c 1549/1550 BCE and so began the New Kingdom. If we allow about 50 years to establish a new regime of record keeping in Saitic Egypt, this would make perfect sense in the context of the story. It is then a matter of sixty years or so back to the devastation of the Minoan Eruption of Thera at the earliest stages of the Late Bronze Age which marks the end of long-running hostilities in the Aegean. These hostilities are evidenced by the archaeology of Kolonna on the island of Aegina–in the Saronic Gulf between Attica and the Peloponnese–which shows a long sequence of destructions and the overlaying of one culture on another.

# Discussion Pending:-

The question of how a mistranslation of these large numbers occurred is an interesting one and can be reasonably resolved by examining the ancient numbering systems on either side of the Mediterranean Sea.

Note: It can be logically argued that this conflict gave rise to the Late Bronze Age and ultimately, the rise of the Mycenaean culture.

The continuation of the relationship between the Aegean sphere and Egypt via Sais is of the utmost importance to the story.

# Discussion Pending:-

Of the combatants on the one side, the city of Athens was reported to have been the leader and to have fought out the war; the combatants on the other side were commanded by the kings of Atlantis,…

For many commentators, the times given for the institution of Athens being the same as for the declaration of war between the Atlanteans and the Athenians creates a real problem. This might not be as incongruous as it seems. The genealogies for the rulers of Athens presented by Apollodorus suggests that they derived from the Aegean Sea and Asia Minor, therefore Athens was in all probability a mainland colony of Anatolian peoples via the Cycladic Islands whereas the Helladic peoples of the Balkan Peninsula would have been related to the northern and western folk.

…which, as I was saying, was an island greater in extent than Libya and Asia,…

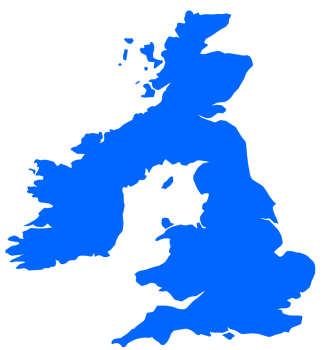

An island being greater in extent than Libya and Asia tends to negate the idea of British Atlantis but I think it’s worth considering that without a modern, technology-based view of the world, ancient navigators would have relied on their perceptions. And, compared to any island in the Mediterranean Sea, Britain is huge. There are several reasons why the ancient perceptions might have been misleading. Judgement of speed and distance would have been developed in the Mediterranean Sea and the convoluted coastline of the British Isles might have given a false idea of the length of the coastline and hence the size of the Island. Alternatively, the mistranslation of large numbers within the story carried back to Greece by Solon may have distorted the supposed sizes of the island.

# Discussion Pending:-

…and when afterwards sunk by an earthquake, became an impassable barrier of mud to voyagers sailing from hence to any part of the ocean.

There is no credible evidence that a barrier of mud preventing access to “any part of the Ocean” ever existed. It has, however been posited that the Phoenician traders spread such a rumour to protect their exclusive access to the Atlantic Ocean; a reasonable proposition.

The progress of the history will unfold the various nations of barbarians and families of Hellenes which then existed, as they successively appear on the scene; but I must describe first of all Athenians of that day, and their enemies who fought with them, and then the respective powers and governments of the two kingdoms.

This passage suggests that Plato never got to finish the dialogues as he seemed intent on naming the various nations involved in the conflict but this never eventuated.

“Let us give the precedence to Athens”

The audience is told the mythical background story of how the gods divided up the earth and how Athena and her brother Hephaestos ‘produced a native race of good men and gave them suitable political arrangements’. Their descendants who survived the destruction preserved the names of the rulers of these Athenians.

For when there were any survivors, as I have already said, they were men who dwelt in the mountains; and they were ignorant of the art of writing, and had heard only the names of the chiefs of the land, but very little about their actions. The names they were willing enough to give to their children; but the virtues and the laws of their predecessors, they knew only by obscure traditions; and as they themselves and their children lacked for many generations the necessaries of life, they directed their attention to the supply of their wants, and of them they conversed, to the neglect of events that had happened in times long past; for mythology and the enquiry into antiquity are first introduced into cities when they begin to have leisure, and when they see that the necessaries of life have already been provided, but not before.

The loss of writing would have to refer to a writing system that existed in the Balkan/Aegean world prior to the destruction of the late 17th century BCE and this needs to be identified. Crete had several systems on-the-go during the pre-palatial second millennium; these were Hieroglyphic and Linear-A scripts, both derived from what is known as the ‘Archanes script’. Oral traditions handed down to the Greeks of classical times when literature emerged in the works of Hesiod, Homer and the likes, were predominantly of Mycenaean origin and were almost certainly sung by bards–a tradition that still exists in isolated pockets of the Balkan Peninsula to this day.

# Discussion Pending:-

In reference to the naming traditions inspired by the Heroic Era, Critias says…

This I infer because Solon said that the priests in their narrative of that war mentioned most of the names which are recorded prior to the time of Theseus, such as Cecrops, and Erechtheus, and Erichthonius, and Erysichthon, and the names of the women in like manner.

This last sentence is perhaps one of the most powerful clues to a credible time-frame for the war. The names Cecrops, and Erechtheus, and Erichthonius, and Erysichthon that were preserved must logically have belonged to the Mycenaean world following the Thera eruption. It is suggested in fragments of the Atthidographers of Athens that “after Ogygos, because of the great destruction caused by the flood, what is now Attike remained without a king until the time of Kekrops”. Ogygos was supposed to have been king of an indigenous pre-Greek tribe. This would mean that Theseus’ story is set in the Late Bronze Age when the Mycenaeans dis-empowered the Minoan civilisation and gained prominence throughout the region. According to Apollodorus, Theseus’ mother, Aethra, was a niece of Atrues, ancestor of Menalaus of Sparta and Agamemnon of Mycenae. Theseus’ father Aegeus was descended from Cecrops, Erechtheus, Erichthonius, etc., back to Deucalion who was in turn descended from Prometheus, the Titan brother of Atlas, further reinforcing the idea that the Caucasians and circum-Pontic peoples were indeed the–perhaps not-so-mythical–Titans.

# Discussion Pending:-

Now the country was inhabited in those days by various classes of citizens;- there were artisans, and there were husbandmen, and there was also a warrior class originally set apart by divine men. The latter dwelt by themselves, and had all things suitable for nurture and education; neither had any of them anything of their own, but they regarded all that they had as common property; nor did they claim to receive of the other citizens anything more than their necessary food. And they practised all the pursuits which we yesterday described as those of our imaginary guardians.

The society described in this passage was far from egalitarian in nature and would have more in common with the large, highly structured, top-down societies of the Fertile Crescent and the largest part of Anatolia. This would be a far cry from the way in which the Caucasians and Circum-Pontic “Titanic” cultures would have conducted themselves. But ultimately it seems top-down governance was mandated by the increase of population and more intense interaction between various groups on the Greek mainland under the influence of the Mycenae.

# Discussion Pending:-

Concerning the country the Egyptian priests said what is not only probable but manifestly true, that the boundaries were in those days fixed by the Isthmus, and that in the direction of the continent they extended as far as the heights of Cithaeron and Parnes; the boundary line came down in the direction of the sea, having the district of Oropus on the right, and with the river Asopus as the limit on the left.

In other words, the Athenians claimed pretty much the whole of the Attic peninsula, adjacent to the Cycladic islands.

Such was the natural state of the country, which was cultivated, as we may well believe, by true husbandmen, who made husbandry their business, and were lovers of honour, and of a noble nature, and had a soil the best in the world, and abundance of water, and in the heaven above an excellently attempered climate.

The physical description of the region included a report on how the land had been degraded from a fertile, well-cultivated area that was once covered in thick woods, to a barren rocky landscape with all of its good soil washed into the sea.

The Acropolis

Now the city in those days was arranged on this wise. In the first place the Acropolis was not as now. For the fact is that a single night of excessive rain washed away the earth and laid bare the rock; at the same time there were earthquakes, and then occurred the extraordinary inundation, which was the third before the great destruction of Deucalion.

One can only try to imagine the states of mind of the various occupants of the region, but it can be assumed there would have been a good deal of reconciliation and reparation between the past protagonists as is evidenced by the cultural exchanges that took place from the early Mycenaean period. In the context of the current hypothesis, Deucalions’ flood was the third major flood after the Minoan eruption of Thera c 1620 BCE.

But in primitive times the hill of the Acropolis extended to the Eridanus and Ilissus, and included the Pnyx on one side, and the Lycabettus as a boundary on the opposite side to the Pnyx, and was all well covered with soil, and level at the top, except in one or two places.

Outside the Acropolis and under the sides of the hill there dwelt artisans, and such of the husbandmen as were tilling the ground near;

Almost all traces of life below the ancient Acropolis would have been erased on the day and night of the catastrophe.

the warrior class dwelt by themselves around the temples of Athene and Hephaestus at the summit, which moreover they had enclosed with a single fence like the garden of a single house. On the north side they had dwellings in common and had erected halls for dining in winter, and had all the buildings which they needed for their common life, besides temples, but there was no adorning of them with gold and silver, for they made no use of these for any purpose; they took a middle course between meanness and ostentation, and built modest houses in which they and their children’s children grew old, and they handed them down to others who were like themselves, always the same.

But in summer-time they left their gardens and gymnasia and dining halls, and then the southern side of the hill was made use of by them for the same purpose. Where the Acropolis now is there was a fountain, which was choked by the earthquake, and has left only the few small streams which still exist in the vicinity, but in those days the fountain gave an abundant supply of water for all and of suitable temperature in summer and in winter.

Given that the catastrophe occurred before the Mycenaean era, it is unlikely that any buildings on the summit of the Acropolis would have survived. There are some traces of pre-Mycenaean archaeology in a few isolated places, particularly in the vicinity of the Olympeion some distance below and to the south-east and the Cerameicos/Keramecos to the west of the Acropolis. The most prominent archaeology on the Acropolis is later than the Thera eruption and ascribed to the Mycenaean era which lasted for about 500 years.

A pre-Mycenaean Athens will be discussed at some length in an essay dedicated to the subject.

This is how they dwelt, being the guardians of their own citizens and the leaders of the Hellenes, who were their willing followers. And they took care to preserve the same number of men and women through all time, being so many as were required for warlike purposes, then as now-that is to say, about twenty thousand

The above statement seems to suggest that the local inhabitants–the Hellenes–were quite happy under the Anatolian rulership; this of course could be seen as pure propaganda.

Twenty thousand members of the military seems extreme and is probably subject to the ten to one error in translation; two thousand might be more realistic.

Such were the ancient Athenians, and after this manner they righteously administered their own land and the rest of Hellas; they were renowned all over Europe and Asia for the beauty of their persons and for the many virtues of their souls, and of all men who lived in those days they were the most illustrious.

If the Thera event and the destruction described by Plato were one and the same, all who lived on the hill that once covered the Acropolis would have been buried or swept away—along with their goods and chattels—in a massive mudslide. This means that any archaeology for the Middle Bronze Age of the region would best take place well below the accepted levels ascribed to ancient Athens and this is limited to about 1600 BCE when the Mycenaean influence appeared. Core samples taken in the low-lying areas of Piraeus (the port of Athens) tell an interesting story of the region before the Athens we know and love.

# Discussion Pending:-

Yet, before proceeding further in the narrative, I ought to warn you, that you must not be surprised if you should perhaps hear Hellenic names given to foreigners. I will tell you the reason of this: Solon, who was intending to use the tale for his poem, enquired into the meaning of the names, and found that the early Egyptians in writing them down had translated them into their own language, and he recovered the meaning of the several names and when copying them out again translated them into our language.

My great-grandfather, Dropides, had the original writing, which is still in my possession, and was carefully studied by me when I was a child. Therefore if you hear names such as are used in this country, you must not be surprised, for I have told how they came to be introduced. The tale, which was of great length, began as follows:-

This process of copying and translating details of stories into local languages highlights the perils of taking ancient texts as absolutely true and correct; yet it must be acknowledged that the basic cores of the stories were in large part conscientiously maintained because it is unlikely they were considered to be fictitious; but rather would have been regarded as important stories of important events. There is also contention surrounding the existence of a written version of the story as Critias previously implied that he heard the story and learned it by heart. This question can potentially be answered in several ways and will never be absolutely resolved but this need not be an impediment to our understanding of the story.

# Discussion Pending:-

The Island

I have before remarked in speaking of the allotments of the gods, that they distributed the whole earth into portions differing in extent, and made for themselves temples and instituted sacrifices. And Poseidon, receiving for his lot the island of Atlantis, begat children by a mortal woman, and settled them in a part of the island, which I will describe.

Poseidon was almost certainly a god of seafaring people from the eastern Mediterranean or the Aegean Sea. There were two basic forms of westward migrations of Neolithic peoples from the sixth millennium BCE. Farmers and graziers spread along the Danube Valley and the Northern Plains who we recognise as the Linear Banded Cultures (LBK). More importantly for this discussion, there were the maritime traders and settlers who ventured into the western Mediterranean, eventually reaching the British Isles via France, the Atlantic coastal regions and Brittany in the late fifth – early fourth millennium about three hundred years before the continental farmers from the Rhine Valley arrived. It can logically be argued that the Impresso/Cardium Culture, worshippers of Poseidon were these first Neolithic traders and settlers from the Mediterranean.

# Discussions Pending:-

Looking towards the sea, but in the centre of the whole island, there was a plain which is said to have been the fairest of all plains and very fertile. Near the plain again, and also in the centre of the island at a distance of about fifty stadia, [50 st = 9.25 km = 5.7 miles] there was a mountain not very high on any side.

The idea of a British Atlantis as a single island greater in extent than Libya and Asia presents a bit of a problem but there are several factors that could explain this anomaly. The statement “[l]ooking towards the sea, but in the centre of the whole island“ can be simply explained if we consider that during the Ice Age, glacial debris was carried down from the Scottish Highlands and deposited in the rift that is the North Channel of the Irish Sea, forming a land-bridge between Ireland and Scotland and forming the Drumlins of Ireland. When the sea level rose high enough to connect the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, the tidal scouring would have rapidly removed the finer particles leaving the rock fields that are a feature of the North Channel to this day. Given this scenario, the Irish Sea would have, in effect, been a gulf in the middle of the whole island and any settlement/’city’ could have been on a plain overlooking the sea in the centre of the island.

In this mountain there dwelt one of the earth born primeval men of that country, whose name was Evenor, and he had a wife named Leucippe, and they had an only daughter who was called Cleito

Poseidon fell in love with her and had intercourse with her, and breaking the ground, inclosed the hill in which she dwelt all round, making alternate zones of sea and land larger and smaller, encircling one another; there were two of land and three of water, which he turned as with a lathe, each having its circumference equidistant every way from the centre, so that no man could get to the island, for ships and voyages were not as yet

First contact with the people of Britain who would have lived a fairly comfortable (primeval) Mesolithic way of life–whatever that might have entailed–but they must have embraced the contact and trade with the new arrivals c 4000 BCE as the new life-ways seem to have been adopted fairly quickly.

The image of concentric alternating ridges and ditches evokes the idea of henges that can be found throughout the British Isles and dating to the earliest Neolithic. The reference to ‘ships’ very likely suggests a distinction between boats with oars or paddles as opposed to larger vessels with sails.

He himself, being a god, found no difficulty in making special arrangements for the centre island, bringing up two springs of water from beneath the earth, one of warm water and the other of cold,

England is well known for its spas and hot springs, so this should not in any way negate the proposition that Britain was Plato’s Atlantis.

# Discussion Pending:-

He also begat and brought up five pairs of twin male children; and dividing the island of Atlantis into ten portions, he gave to the first-born of the eldest pair his mother’s dwelling and the surrounding allotment, which was the largest and best, and made him king over the rest; the others he made princes, and gave them rule over many men, and a large territory.

The cultural influence of the Mediterranean Neolithic traders might have helped establish new, more cooperative ways for the indigenous peoples of Britain to deal with each other in a cooperative, symbolic brotherhood, creating a sense of ‘family’ for the whole island.

And he named them all; the eldest, who was the first king, he named Atlas, and after him the whole island and the ocean were called Atlantic.

This is an important point that is all too often ignored or swept under the carpet because it presents too many problems of logistics and chronology, but there are important clues in the archaeology of prehistory in conjunction with ancient classical stories of the Gods, Titans and other adventuring heroes. The notion of kingship raises questions about how a hierarchical social structure came about among northern Europeans: Either it was introduced by Poseidon from the Mediterranean Sea at the beginning of the British Neolithic; or it was assumed that the later big men of the Kurgan people adopted this role.

To his twin brother, who was born after him, and obtained as his lot the extremity of the island towards the Pillars of Heracles, facing the country which is now called the region of Gades in that part of the world, he gave the name which in the Hellenic language is Eumelus, in the language of the country which is named after him, Gadeirus.

Under the present hypothesis with regard to the perceived location of the island, the western part of the island (still connected to the main island by a glacial debris land-bridge?), aka Ireland, this would indeed be the closest point to the region of Gades/Gadeira.

Of the second pair of twins he called one Ampheres, and the other Evaemon. To the elder of the third pair of twins he gave the name Mneseus, and Autochthon (indigenous) to the one who followed him. Of the fourth pair of twins he called the elder Elasippus [Resilient ?], and the younger Mestor. And of the fifth pair he gave to the elder the name of Azaes, and to the younger that of Diaprepes [Eminent].

If the five sets of twins were the symbolic representatives of provinces within the island as logic would dictate; the first born of each of the twins could represent provinces of the main part of the island headed by Atlas, and the second born of the twins would represent the provinces of the smaller part of the island headed by Eumelus. Irish mythology claims there were five ancient provinces in Ireland. If Albion (England), the main island that we recognise today was also divided into five provinces, then this would make perfect sense in the context of the story. Casting the elites or rulers of the various provinces as sets of twins and a cohort of brothers might have been a matter of expediency in the interests of peace and cooperation.

It’s a very interesting fact that the trilithons of Stonehenge comprise five sets of two standing stones connected by lintels. And since it is widely held that the standing stones of Atlantic Europe represent persons of great prestige, it is not too great a stretch to consider the trilithons as representing the ten rulers of the ten provinces of Britain.

All these and their descendants for many generations were the inhabitants and rulers of divers islands in the open sea; and also, as has been already said, they held sway in our direction over the country within the Pillars as far as Egypt and Tyrrhenia.

The area over which the Atlanteans held sway, corresponds remarkably well with the distribution of Beaker Burial archaeology.

Now Atlas had a numerous and honourable family, and they retained the kingdom, the eldest son handing it on to his eldest for many generations; and they had such an amount of wealth as was never before possessed by kings and potentates, and is not likely ever to be again, and they were furnished with everything which they needed, both in the city and country.

For because of the greatness of their empire many things were brought to them from foreign countries, and the island itself provided most of what was required by them for the uses of life.

The Wessex culture of Britain c 2050-1700 BCE became the wealthiest community in Europe; no doubt due to the rich tin resources and the extremely high quality of bronze produced on the island. The Salisbury Plain was an important sacred landscape visited by people from all over Europe. As an important part of the Beaker network, they would have enjoyed a great deal of prestige.

# Discussion Pending:-

Resources

In the first place, they dug out of the earth whatever was to be found there, solid as well as fusile, and that which is now only a name and was then something more than a name, orichalcum, was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island, being more precious in those days than anything except gold.

Orichalcum is one of the major sources of debate in the story as there is no universal acceptance of what it really was. I personally do not understand why there has been such vehement disagreement as to it’s nature. The name itself suggests what it is: Orum/Aurum must refer to the element of gold; Calcum almost certainly denotes copper. Hence, the name oricalcum refers to a native alloy of gold and copper to which we refer today as red or pink gold. A further confirmation of this suggestion is that in the myths and legends of Ireland, many heroes were awarded trophies of ‘red gold’.

There was an abundance of wood for carpenter’s work, and sufficient maintenance for tame and wild animals. Moreover, there were a great number of elephants in the island; for as there was provision for all other sorts of animals, both for those which live in lakes and marshes and rivers, and also for those which live in mountains and on plains, so there was for the animal which is the largest and most voracious of all.

The mention of elephants has always created a barrier to the acceptance of Britain as Atlantis, but it should be borne in mind that woolly mammoth frequented the Thames Valley from the Last Glacial Maximum, and the European straight-tusked elephant occupied the region during the last Interglacial period. It is perfectly reasonable to assume that fossil ivory was exported from this area – hence the idea that elephants lived and thrived in Atlantis.

Also whatever fragrant things there now are in the earth, whether roots, or herbage, or woods, or essences which distil from fruit and flower, grew and thrived in that land; also the fruit which admits of cultivation, both the dry sort, which is given us for nourishment and any other which we use for food-we call them all by the common name pulse, and the fruits having a hard rind, affording drinks and meats and ointments, and good store of chestnuts and the like, which furnish pleasure and amusement, and are fruits which spoil with keeping, and the pleasant kinds of dessert, with which we console ourselves after dinner, when we are tired of eating-all these that sacred island which then beheld the light of the sun, brought forth fair and wondrous and in infinite abundance. With such blessings the earth freely furnished them;

There can be no doubt that Critias’ description of the island could apply to Britain; ‘a green and pleasant land’. The descriptions of all the produce mentioned above can easily be understood as fruits and vegetables native to temperate Europe including England.

#Discussion Pending:-

meanwhile they went on constructing their temples and palaces and harbours and docks. And they arranged the whole country in the following manner:

Metropolis

First of all they bridged over the zones of sea which surrounded the ancient metropolis, making a road to and from the royal palace. And at the very beginning they built the palace in the habitation of the god [Poseidon] and of their ancestors, which they continued to ornament in successive generations, every king surpassing the one who went before him to the utmost of his power, until they made the building a marvel to behold for size and for beauty.

And beginning from the sea they bored a canal of three hundred feet in width and one hundred feet in depth and fifty stadia in length, [50 stadia = 9.25 km = 5.7 miles] which they carried through to the outermost zone, making a passage from the sea up to this, which became a harbour, and leaving an opening sufficient to enable the largest vessels to find ingress.

The measurements given for width and depth of the channels might be affected by the ‘hundreds for tens mistranslation of large numbers‘ which would make the channel thirty feet wide and ten feet deep–a much more believable size.

In Plato’s time, the Greeks were building ships up to 10m / 30ft wide, and perhaps up to 100m long, but prior to this, ships seemed to rarely exceed 5m / 15ft wide by 35m / 110?ft long and one can only assume that ships would have been smaller than this in earlier times. So, if there is any validity at all in this part of the story, the channels would have been adequate at 30ft wide. There is also a possibility that Plato’s own imaginings were at play here, based on his own world view and expectations regarding this part of the story.

Moreover, they divided at the bridges the zones of land which parted the zones of sea, leaving room for a single trireme to pass out of one zone into another, and they covered over the channels so as to leave a way underneath for the ships; for the banks were raised considerably above the water. Now the largest of the zones into which a passage was cut from the sea was three stadia in breadth [3 st = 555 meters], and the zone of land which came next of equal breadth; but the next two zones, the one of water, the other of land, were two stadia, [2 st = 370 meters] and the one [1st = 185m] which surrounded the central island was a stadium only in width. The island in which the palace was situated had a diameter of five stadia [5 st = 925 meters]. All this including the zones and the bridge, which was the sixth part of a stadium [1/6 = 31 metres] in width, they were surrounded by a stone wall on every side, placing towers and gates on the bridges where the sea passed in.

In reality, the works described here, do not seem to match anything found so far in Britain. There are however, many sophisticated fortifications throughout the southern and central Iberian Peninsular dating to the third millennium BCE. Descriptions of these fortresses of trade would certainly have found their way back to the opposite end of the Mediterranean. It takes only a small leap of imagination to see how the stories of these various major works in Atlantic Europe became conflated to create the picture presented by Plato. Whether this is a description cobbled together by Plato or it was part of the story carried by Solon back to Greece from Egypt is anyone’s guess, but the Beaker culture of Britain is thought largely to have originated in Iberia which could account for how peoples of the East would have identified people as far away as the Atlantic coast.

There is a surfeit of modern reconstructions of the ‘city of Atlantis’ and so, this avenue will not be pursued further here except to demonstrate the practical affects of the hundreds for tens error in translation with regard to the geography of the plain and ‘city’.

# Refer:- Overview – Numbers

The stone which was used in the work they quarried from underneath the centre island, and from underneath the zones, on the outer as well as the inner side. One kind was white, another black, and a third red, and as they quarried, they at the same time hollowed out double docks, having roofs formed out of the native rock. Some of their buildings were simple, but in others they put together different stones, varying the colour to please the eye, and to be a natural source of delight. The entire circuit of the wall, which went round the outermost zone, they covered with a coating of brass [bronze?], and the circuit of the next wall they coated with tin, and the third, which encompassed the citadel, flashed with the red light of orichalcum.

It would be foolish to dismiss these descriptions out of hand despite the fact it seems to be on a par with the cities with ‘streets paved with gold’ stories. That being said, there are many credible ways such apparent grandeur can be explained. Rubbing or burnishing the surfaces of stonework with metallic ores could have such an effect, likewise mixing particles of metal in paint or plaster is also a possibility. Whatever the case might be, the answers are beyond certainty and in truth, do not have a great deal of impact on the over-all debate.

The palaces in the interior of the citadel were constructed on this wise:-in the centre was a holy temple dedicated to Cleito and Poseidon, which remained inaccessible, and was surrounded by an enclosure of gold; this was the spot where the family of the ten princes first saw the light, and thither the people annually brought the fruits of the earth in their season from all the ten portions, to be an offering to each of the ten. Here was Poseidon’s own temple which was a stadium in length, and half a stadium in width [185 x 92 m], and of a proportionate height, having a strange barbaric appearance. All the outside of the temple, with the exception of the pinnacles, they covered with silver, and the pinnacles with gold. In the interior of the temple the roof was of ivory, curiously wrought everywhere with gold and silver and orichalcum; and all the other parts, the walls and pillars and floor, they coated with orichalcum. In the temple they placed statues of gold: there was the god himself standing in a chariot-the charioteer of six winged horses-and of such a size that he touched the roof of the building with his head; around him there were a hundred Nereids riding on dolphins, for such was thought to be the number of them by the men of those days. There were also in the interior of the temple other images which had been dedicated by private persons. And around the temple on the outside were placed statues of gold of all the descendants of the ten kings and of their wives, and there were many other great offerings of kings and of private persons, coming both from the city itself and from the foreign cities over which they held sway. There was an altar too, which in size and workmanship corresponded to this magnificence, and the palaces, in like manner, answered to the greatness of the kingdom and the glory of the temple.

The description of Poseidon’s temple having a ‘strange barbaric appearance’ is a very telling point; likewise for the ‘statue’ of Poseidon touching the roof of the building. It can fairly be assumed of any ‘statue’ in western Europe during the Neolithic and early Bronze Ages that the sculpting of such an object would have looked more like a totem or spirit pole, the likes of which are evidenced from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast and on to the Americas. In fact they seem to be universal throughout the world in societies with shamanistic-like practices. Stylistically any such object would have been unimaginable to Plato and the world he inhabited; so I guess he could be forgiven for the grandiose descriptions of the temple surrounding structures. It should be said that the statue touching the roof would most likely, have been holding the roof up. Again, these conjectures do not necessarily have any great influence on the over-all discussion.

In the next place, they had fountains, one of cold and another of hot water, in gracious plenty flowing; and they were wonderfully adapted for use by reason of the pleasantness and excellence of their waters. They constructed buildings about them and planted suitable trees, also they made cisterns, some open to the heavens, others roofed over, to be used in winter as warm baths; there were the kings’ baths, and the baths of private persons, which were kept apart; and there were separate baths for women, and for horses and cattle, and to each of them they gave as much adornment as was suitable. Of the water which ran off they carried some to the grove of Poseidon, where were growing all manner of trees of wonderful height and beauty, owing to the excellence of the soil, while the remainder was conveyed by aqueducts along the bridges to the outer circles; and there were many temples built and dedicated to many gods;…

The Desmond Lee translation mentions of hot and cold springs rather than fountains which implies a natural geological phenomenon. Anyone who has been to England would be aware of the therapeutic springs available there.

…also gardens and places of exercise, some for men, and others for horses in both of the two islands formed by the zones; and in the centre of the larger of the two there was set apart a race-course of a stadium [185m] in width, and in length allowed to extend all round the island, for horses to race in. Also there were guardhouses at intervals for the guards, the more trusted of whom were appointed-to keep watch in the lesser zone, which was nearer the Acropolis while the most trusted of all had houses given them within the citadel, near the persons of the kings. The docks were full of triremes and naval stores, and all things were quite ready for use. Enough of the plan of the royal palace.

Domesticated horses were not present in Atlantic Europe until about the middle of the 3rd millennium when they arrived–along with the wheel–in the west with the Bronze Age Eurasians who radically extended the trading networks across Europe.

# Discussion Pending:-

Leaving the palace and passing out across the three you came to a wall which began at the sea and went all round: this was everywhere distant fifty stadia [9.25 km]from the largest zone or harbour, and enclosed the whole, the ends meeting at the mouth of the channel which led to the sea. The entire area was densely crowded with habitations; and the canal and the largest of the harbours were full of vessels and merchants coming from all parts, who, from their numbers, kept up a multitudinous sound of human voices, and din and clatter of all sorts night and day.

Desmond Lee’s translation has this wall ‘densely built up all round with houses‘ which tends to suggest the houses were close to, or were built into the wall, not unlike many of the Bronze Age forts of Iberia. This might also be a case of images and impressions from the Atlantic region being melded together. The romance of exotic faraway places seems to engender scenes of excitement and hustle and bustle which might or might not be true; but it certainly is true that any island involved in a wide trading network would have some pretty busy ports, and this was probably the case in Bronze Age Britain.

The rest of the island

I have described the city and the environs of the ancient palace nearly in the words of Solon, and now I must endeavour to represent the nature and arrangement of the rest of the land. The whole country was said by him to be very lofty and precipitous on the side of the sea,

A photo-tour of the British coastlines will leave one with the impression that they are ” very lofty and precipitous on the side of the sea”. Any approach to the British Isles from the Continent or the Atlantic Ocean would be met with high cliffs giving the impression that the ‘island’ is well above sea-level. The fact that this feature rates a special mention suggests some novelty distinct from what can be seen in the Mediterranean coastlines. There are of course plenty of cliffs in the Mediterranean, particularly where the islands are concerned; but these relatively small islands must have been considered differently from the mainlands surrounding the Mediterranean, the majority of whose coastlines seem to be near sea-level with mountains forming a backdrop in the distance. This height above sea-level is no doubt due to the isostatic lifting of Britain when the over-burden of the glaciers melted away during the Holocene.

but the country immediately about and surrounding the city was a level plain, itself surrounded by mountains which descended towards the sea; it was smooth and even, and of an oblong shape, extending in one direction three thousand stadia [555 km = 342 miles], but across the centre inland it was two thousand stadia [370 km = 228 miles] .

If the plain really was 555 km by 370 km it would be impossible to determine that it was surrounded by mountains because, due to the curvature of the Earth any mountains would not be visible without the aid of some very sophisticated modern equipment. If we divide these numbers by a factor of ten, we will end up with a much more credible view of the plain at roughly 55 km by 37 km. These dimensions could easily fit within several locations around the Irish Sea.

This part of the island looked towards the south, and was sheltered from the north. The surrounding mountains were celebrated for their number and size and beauty, far beyond any which still exist, having in them also many wealthy villages of country folk, and rivers, and lakes, and meadows supplying food enough for every animal, wild or tame, and much wood of various sorts, abundant for each and every kind of work.

Neolithic life-ways in the British Isles was not the result of just one single event, but was introduced at various times from various locations from the Bay of Biscay to Denmark. Some of the earliest evidence for settlement is found in the north-eastern corner of Ireland and the west coast of Scotland in the Firth of Clyde area at the head of the Irish Sea; and this raises some very interesting ideas as to the location of Cleito’s home. Any glacial landfill between Scotland and Ireland would have been extremely fertile and this would account for the early agricultural settlement in this area.

# Refer:- Overview; The Island – problems of scale and location

I will now describe the plain, as it was fashioned by nature and by the labours of many generations of kings through long ages. It was for the most part rectangular and oblong, and where falling out of the straight line followed the circular ditch. The depth, and width, and length of this ditch were incredible, and gave the impression that a work of such extent, in addition to so many others, could never have been artificial. Nevertheless I must say what I was told. It was excavated to the depth of a hundred, feet, and its breadth was a stadium everywhere; it was carried round the whole of the plain, and was ten thousand stadia in length. It received the streams which came down from the mountains, and winding round the plain and meeting at the city, was there let off into the sea. Further inland, likewise, straight canals of a hundred feet in width were cut from it through the plain, and again let off into the ditch leading to the sea: these canals were at intervals of a hundred stadia, and by them they brought down the wood from the mountains to the city, and conveyed the fruits of the earth in ships, cutting transverse passages from one canal into another, and to the city. Twice in the year they gathered the fruits of the earth;– in winter having the benefit of the rains of heaven, and in summer the water which the land supplied by introducing streams from the canals.

Critias/Plato is very sceptical of the vastness of the plain and the works of engineering, even compared to the sophistication of the world in which he/they lived; and of course this is yet another case for a translational error concerning large numbers–so let’s look at these numbers:

The surrounding ditch was 10,000 stadia in length; this equals 1850 km or 1140 miles, which if divided by ten would be 185 km or 114 miles, dug to a depth of 10 feet by 1/10th of a stadium equivalent to 18.5 metres or 20 yards wide. Even with a 1/10th correction, this part of the description still stretches credibility to the limit. Descriptions of the straight ditches, if divided by 10 (i.e. 10 feet wide and 10 stadia apart) make a lot more sense and seem quite similar to the way in which the British field systems were configured.

Military

As to the population, each of the lots in the plain had to find a leader for the men who were fit for military service, and the size of a lot was a square of ten stadia each way, and the total number of all the lots was sixty thousand. And of the inhabitants of the mountains and of the rest of the country there was also a vast multitude, which was distributed among the lots and had leaders assigned to them according to their districts and villages. The leader was required to furnish for the war the sixth portion of a war-chariot, so as to make up a total of ten thousand chariots; also two horses and riders for them, and a pair of chariot-horses without a seat, accompanied by a horseman who could fight on foot carrying a small shield, and having a charioteer who stood behind the man-at-arms to guide the two horses; also, he was bound to furnish two heavy armed soldiers, two slingers, three stone-shooters and three javelin-men, who were light-armed, and four sailors to make up the complement of twelve hundred ships. Such was the military order of the royal city-the order of the other nine governments varied, and it would be wearisome to recount their several differences.

This section quantifying military obligations of the Atlanteans as translated by two modern scholars; namely Benjamin Jowett and Desmond Lee illustrates how easily misinterpretations can occur. Jowett gives the size of each lot/allotment as 10 stades square, which means that each lot was 100 square stades, 10 times larger than the area given by the Lee who gives each allotment as 10 square stades. The numbers as given in the Critias texts are extreme and the division of all large numbers by ten makes the situation much more believable. The identities of the combatants against Athens require a much more nuanced approach than simply coming from Atlantis. As expressed in the dialogues, there were many groups of people involved in the conflict.

# Refer:- Overview – Military obligations

Offices and honours

The following passage has been divided up and trimmed a little for the sake of brevity and in order to focus on the most relevant aspects of their nature.

As to offices and honours, the following was the arrangement from the first. Each of the ten kings in his own division and in his own city had the absolute control of the citizens, and, in most cases, of the laws, punishing and slaying whomsoever he would.

This is a statement suggesting divinely sanctioned authority within the jurisdiction of the king which suggests a scheme introduced from the Mediterranean Sea.

…the commands of Poseidon which the law had handed down. These were inscribed by the first kings on a pillar of orichalcum, which was situated in the middle of the island, at the temple of Poseidon, whither the kings were gathered together every fifth and every sixth year alternately, thus giving equal honour to the odd and to the even number.

And when they were gathered together they consulted about their common interests, and enquired if any one had transgressed in anything and passed judgement and before they passed judgement they gave their pledges to one another on this wise:-

These meetings during the reign of any individual king would have occurred, on average, only four to six times; so their autonomy would have been considerable and judgement of their actions, rare but perhaps adequate for keeping the peace.

There were bulls who had the range of the temple of Poseidon; and the ten kings, being left alone in the temple, after they had offered prayers to the god that they might capture the victim which was acceptable to him, hunted the bulls, without weapons but with staves and nooses;

Vapheio cups illustrate this scene with extraordinary accuracy and it can be noticed that the interaction between people and the bulls is radically different from the depictions of the Minoan bull leapers. Stylistically too, the craftsmanship does not look particularly Minoan despite the fact that the Mycenaeans adopted with relish, the stylings of Minoan artisans.

…and the bull which they caught they led up to the pillar and cut its throat over the top of it so that the blood fell upon the sacred inscription. Now on the pillar, besides the laws, there was inscribed an oath invoking mighty curses on the disobedient.

…after slaying the bull …they had burnt its limbs, they filled a bowl of wine and cast in a clot of blood for each of them; the rest of the victim they put in the fire, after having purified the column all round …they drew from the bowl in golden cups and pouring a libation on the fire, they swore that they would judge according to the laws on the pillar, and would punish him who in any point had already transgressed them, and that for the future they would not, if they could help, offend against the writing on the pillar, and would neither command others, nor obey any ruler who commanded them, to act otherwise than according to the laws of their father Poseidon.

…after they had supped and satisfied their needs, when darkness came on, and the fire about the sacrifice was cool, all of them put on most beautiful azure robes, and, sitting on the ground, at night, over the embers of the sacrifices by which they had sworn, and extinguishing all the fire about the temple, they received and gave judgement, if any of them had an accusation to bring against any one; and when they given judgement, at daybreak they wrote down their sentences on a golden tablet, and dedicated it together with their robes to be a memorial.

Woad was, and still is in certain parts of Britain, a favoured blue vegetable dye for fabrics; it was used extensively in the past by the Picts and Scots to decorate the body.

Receiving and passing judgement in the dark might have been a way of avoiding personal resentments and vendettas.

…They were not to take up arms against one another, and they were all to come to the rescue if any one in any of their cities attempted to overthrow the royal house; like their ancestors, they were to deliberate in common about war and other matters, giving the supremacy to the descendants of Atlas. And the king was not to have the power of life and death over any of his kinsmen unless he had the assent of the majority of the ten.

It can’t be determine if these mores were actually in place in Atlantis or were Plato’s own theories on how to conduct a peaceful, functioning society. It is beyond doubt that Plato’s views on politics and governance would have found their way into all of his dialogues and T&C would certainly have been no exception but this does not negate the basic underlying veracity of his reconstruction of history based on the stories handed down from the Mycenaean age.

Such was the vast power which the god settled in the lost island of Atlantis; and this he afterwards directed against our land for the following reasons, as tradition tells:

The Fall: a reason for war

This passage has been divided up and trimmed a little for the sake of brevity in order to concentrate on the main reasons for the decline.

For many generations, as long as the divine nature lasted in them, they were obedient to the laws, and well-affectioned towards the god, whose seed they were;

[T]hey possessed;… great spirits… gentleness with wisdom…. They despised everything but virtue… thinking lightly of the possession of gold and other property,… they were sober, and saw clearly that all these goods are increased by virtue and friendship with one another… By such reflections and by the continuance in them of a divine nature, the qualities which we have described grew and increased among them;

Development in Britain subsequent to the arrival of neolithic peoples from the Mediterranean Sea c 4000 BCE, can be seen in the appearance of henges in sacred spaces. Standing stones arrays in and around the Atlantic seaboard, in many cases replaced timber structures–e.g. Stonehenge among others. A unique blending of indigenous and imported traditions resulted in new and dynamic religious practices and monument building. This period also gave rise to the flowering of the Beaker Burial traditions of trade and connection across western and central Europe.

but when the divine portion began to fade away, and became diluted too often and too much with the mortal admixture, and the human nature got the upper hand, they then, being unable to bear their fortune, behaved unseemly, and to him who had an eye to see grew visibly debased… to those who had no eye to see the true happiness, they appeared glorious and blessed at the very time when they were full of avarice and unrighteous power.

From the third millennium, the Kurgan/Yamnaya cultures from the Pontic and steppe regions began to influence and aggressively expand the existing trade networks with the introduction of the horse and wheel, and a new bronze metallurgy. It can be argued that the influences of these aggressive new traders were instrumental in introducing a venal and irreligious element to Europe. Hence, the moral decline of the Atlanteans.

# Discussion Pending:-

Zeus, the god of gods, who rules according to law, and is able to see into such things, perceiving that an honourable race was in a woeful plight, and wanting to inflict punishment on them, that they might be chastened and improve, collected all the gods into their most holy habitation, which, being placed in the centre of the world, beholds all created things. And when he had called them together, he spake as follows- * The rest of the Dialogue of Critias has been lost… …if it was ever written.

I think it’s important to note that ‘the Gods’ are associated with kingship and top-down, highly structured authority which seems not to have been the case for the northern Eurasian peoples. Decentralised, competitive rough and tumble of the north must surely have been considered degenerate and undesirable by the ‘highly cultured’ people who claimed descent from the gods. Hence, the degeneration of once godly/kingly societies that existed in the far west under the tutelage of Poseidon and his representatives.