Plato: Life and Times

“Truth, Stranger, is a noble thing and a lasting, but a thing

of which men are hard to be persuaded.”

(Cleinias, a Cretan to the Athenian in Laws, Plato.

Translated by Benjamin Jowett).

Abstract

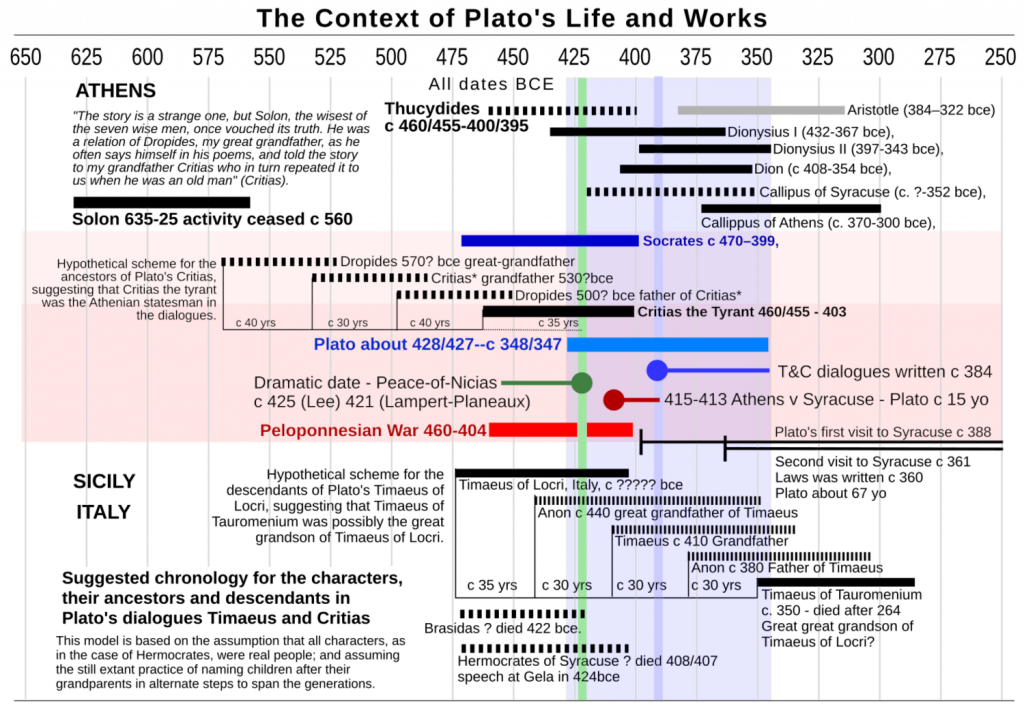

Plato was born into a wealthy and influential Athenian family in the middle of the second Peloponnesian War between two super powers and their allies involving the whole of Greece from the Aegean western limits of the Persian empire to Sicily and Italy and had been going for about thirty five years. He was about three years old at the time of the Peace of Nicias which is also approximately the Dramatic Date of his Timaeus and Critias dialogues which he wrote in his later life. Ever since he wrote these dialogues rather fierce debates have raged over the veracity of the story presented by Critias of a war between an ancient Athenians and a mysterious peoples from an island in the Atlantic Ocean. All the main characters of the dialogues and the various people Plato had dealings with in the context of the Peloponnesian war and after, can be verified to some degree. The big question is; whether or not, the events surrounding these individuals really occurred. The works of Thucydides, Plutarch and others rarely come in for the same level of scepticism as do the Timaeus and Critias dialogues; somewhat unfairly in this writer’s opinion.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to look at the circumstances and events that influenced Plato and drove his obsession with philosophy and ‘right education’ as a means to achieving good government and a good society. No doubt it was this lifelong obsession behind the writing of Timaeus and Critias. Many of the dates and corresponding alignment with historical events of Plato’s lifetime are broadly accepted by established scholarship while many others are approximations or best guesses. The majority of dates and profiles of the characters and relationships involved in the dialogues are taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica (Constance C. Meinwald, last up-dated in 2017), the Ancient History Encyclopaedia – Peloponnesian War Timeline, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, to a small degree, the works of Plutarch, and the works and epistles of Plato himself; although there is much debate over the authenticity of some of his letters, the basic information contained therein is taken on faith as being at the very least, plausible.

The identities and relationships within Plato’s world will be examined. It is also important to try to understand why Hermocrates–birth date unknown and died c 408/407 BCE–although intended as the presenter of the third dialogue, was not included among the final lineup. Many scholars believe the Laws deals with the subject matter that was to be covered by Hermocrates. The characters of Solon, Socrates, Hermocrates and to some extent, Critias are accepted as historical figures, but Timaeus has not been reliably established as a historical person; he is the subject of much debate and will be discussed at some length.

In spite of the fact in all his other works he takes great pains to make sure he is understood correctly, it seems the acceptance of Plato’s insistence that the story of Atlantis is a true one is impeded by some anomalous features of the the story that cannot be reconciled under existing received wisdom.

Plato’s family and background

Plato was born in Athens about 428/427 BCE and died c 348/347 BCE. He was a star pupil of the great philosopher Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE), and he was the teacher of Aristotle (384–322 BCE). Plato’s father was Ariston who claimed descent from the god Poseidon, which suggests royal descent; this claim deserves further discussion on the ethnicity of the paternal side of Plato’s family. The name of his mother ‘Perictione’ suggests a possible familial or ethnic connection to the great statesman Pericles who died the year before Plato was born. Also of interest; Critias and Charmides, two of his mother’s relatives were among the Thirty Tyrants who were installed by Sparta into a position of power in Athens between 404 and 403 BCE at the end of the Peloponnesian War (Plato’s seventh Epistle) and were discharged in disgrace due to abuse of their positions for personal gain (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Life, Circumstance and Context

Meinwald’s Britannica article skates over the Critias with the statement it ‘is a barely started sequel to the Timaeus; its projected content is the story of the war of ancient Athens and Atlantis‘. This seems to neglect the importance and value of the Critias, and indeed, what was intended as a trilogy “Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates” as a whole; perhaps in part as a reflection of the Peloponnesian Wars. It’s important to consider Plato’s life and experiences in this context because he was born in the middle of the Peloponnesian wars (460-404 BCE), and the period in which the dialogues were set was during a time of truce, the “Peace of Nicias”–when Plato was a child–and no doubt high level diplomacy between Athens and Sparta and the Peloponnesian colonists to the west was of the highest priority. By the time Plato wrote T&C toward the end of his life, all the politics and violence of the Peloponnesian War would have been very familiar recent history, and in parts, even lived experiences. Perhaps the greatest influence on his thinking was close to home. The despotic behaviour of the Thirty Tyrants, some of whom were his close relatives was a great concern to Plato and would no doubt have influenced the form of the dialogues which developed over most of his lifetime and influenced his thinking as to what constitutes a good and decent society.

The question needs to be asked; were the three dialogues of Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates intended as a diplomatic attempt at fence-mending and peace-making in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War by demonstrating the contributions the representatives of the various groups involved could bring to the benefit of all? If the dialogues were written c 348 BCE as is commonly held, about 77 years after the dramatic date of the dialogues (c 425 BCE) and 56 years after a kind of peace was achieved ending the war between Athens and Sparta, it might be possible to deduce just why Hermocrates seems to have been dropped from the trilogy. Plato’s Seventh Letter (to the relatives and friends of Dion), thought to have been written c 360 BCE gives a good insight as to why this might have happened.

The Seventh Letter

There is much debate about the authenticity of Plato’s Epistles; in particular, the seventh letter that was apparently written as an explanation of events arising from Plato’s interactions with the ruling tyrants of Syracuse. The characters mentioned in the letter, Dionysius I (432-367 BCE), Dionysius II (397-343 BCE), Dion c 408-354 BCE (Britannica); his “friend”–a murderer–Callippus who ruled Syracuse from 354 to 352 BCE and who was himself murdered a short time afterwards in Italy (Plutach’s Dion). There was another Callippus who studied at the Athens Academy, born in Cyzicus, a city on the coast of the Sea of Mamara, a Greek astronomer and mathematician who studied at Plato’s Academy and worked also with Aristotle at the Lyceum in Athens (Callippus in Britannica). Both were historical figures linked in one way or another with Plato; the latter two as his students at the Academy. There is some confusion or misinterpretation concerning the two identities of Callippus as both are given as attended Plato’s Academy at roughly the same time except, Callippus of Syracuse was murdered in 352 BCE in Italy; and Callippus of Athens (c 370-300 BCE) died a celebrated astronomer (Britannica). This suggests the two were connected; and since Callippus of Athens was probably about fifty years younger than Callippus of Syracuse they might have been grandfather and grandson. See figure 1.

The fact that all the above characters are documented in the ancient works of Plutach, Diodorus and Athenaeus, suggests at least some element of truth in the epistle; although the possibility exists that the letter was written from legendary sources with embellishments by someone other than Plato. This is not an uncommon phenomenon where folk heroes are concerned. From a superficial reading of this seventh letter, Plato seems to have had little doubt about his importance and value to the Greek world expressed in the words, ‘I came to Sicily with the reputation of being by far the most eminent of those engaged in philosophy‘; and although there seems to have been good reason for this opinion, such boastful language might give cause to doubt the authenticity of the letter; after all, someone who almost always spoke through other characters and rarely in his own voice would be expected to be perhaps a little more modest. So it’s possible that the letter was composed or embellished, based on an extant story or legend, by an avid admirer of Platonic philosophy; in which case, it might be perfectly valid to assume the letter does, in large part contain some truth which fits broadly into the historical scheme of this period in classical Greek history.

The story of Plato’s first visits to Sicily told in the Seventh Epistle, if true, tells of a lost hope in being able to alter the course of the entrenched government of Athens over the mainland and Aegean islands, and he accepted Dion’s invitation to teach his philosophy in the newer colonies of Italy and Sicily in the hope of establishing a new, better form of government; he writes ‘I, an Athenian and friend of Dion, came as his ally to the court of Dionysios, in order that I might create good will in place of a state war‘. This, his first visit to the west Plato alleges, took place when he was about forty years of age c 388 BCE. Unfortunately Plato became embroiled in the intrigues of Dionysios the younger against Dion, and suffered rough treatment at the hands of Dionysios II at Syracuse. His early letters to Dionysios reveal frustration and disappointment in his attempts, along with Dion–an enthusiastic student of philosophy and brother-in-law of Dionysius the Elder–to educate Dionysius the Younger in the ways of good government (Britannica).

The second visit took place in 361 BCE when Plato was about 67 years of age (Epistle 3) was at the request of Dionysius whose behaviour towards him proved to be manipulative and duplicitous, rendering his efforts to establish good government in Sicily, entirely fruitless. Plato obviously gave up trying to achieve good government in Sicily as a bad job; and this would be a very likely a reason for not using Syracuse as an exemplar for a well-governed state, and consequently omitted Hermocrates from his dialogues.

The Dramatic Date

Socrates was about 45 years old and Plato would have been about three years old when the Peace of Nicias was established; he was about twelve years old in 413 BCE when the Athenian fleet invaded Sicily and was destroyed by the Peloponnesian colonists of Syracuse under the leadership of Hermocrates. By the end of the Peloponnesian War when he was a young man about 23 years of age there was a brief period of the Thirty Tyrants of Athens–some of whom were related to Plato– after the end of hostilities were installed into power by the victorious Spartans. The resulting corruption of the Tyrants in Athens, created a great disenchantment in Plato with the affairs of men, and this lead him on a life-long quest to find the best form of government for the best kind of society.

Lampert and Planeaux, (1998) claim 421 BCE as the dramatic date for the dialogues. By 425-421 BCE, the Peloponnesian War would have been raging for thirty-five to thirty-nine years and it was about this time with the Peace of Nicias in March of 421 BCE took place and it would be expected that some fairly intense diplomacy would have taken place by then;- ‘It was a period in which diplomatic manoeuvres gradually gave way to small-scale military operations as each city tried to win smaller states over to its side‘ (Britannica, Peace-of-Nicias. Thuc., bk. V ch. XV). The war continued for about another ten years and the Athenians were still trying to dominate Sparta and the Peloponnesian colonies. In 415 Athens launched a massive assault against Sicily and the Athenian fleet was utterly destroyed in 413 BCE, after which the war continued for another ten years or so.

The really big question is; were the ‘Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates‘ dialogues an attempt by Plato to soothe a simmering distrust between the Dorians and the Ionians after the events of the war? Or could the story could simply have been used to extol the virtues of Athenian benevolence to the Peloponnesians. There might have been a recognition or identification of the Peloponnesians with the “Atlantians” and northern Europeans; suggesting a certain moral debt owed by the westerners. Either way, the debate over the veracity of the story is still not solved.

In view of the lack of any direct evidence confirming the story, the only recourse seems to be to try and match the many descriptions given by Plato of the geography, cultures and technologies involved in the war between Athens and Atlantis with what is known about the late prehistory of Europe and the Mediterranean through archaeology and modern scholarship; and this is the aim of this essay.

Thucydides: The History of the Peloponnesian War

Thucydides was born at Alimos, on the coast south of Athens in about 460 BCE or earlier and died after 404 BCE (Encyclopaedia Britannica); The Ancient History Encyclopedia has his birth as c. 460/455 BCE and his death dating to 399 or 398 BCE at the age of about 60 to 65 years. He was a general in the Athenian military and wrote his History of the Peloponnesian War, the last chapter of which was written in 411 BCE, about six years before the war finally ended.

Thucydides’ birth coincided roughly with the beginning of the First Peloponnesian War. After just fourteen years the ‘Thirty Years of Peace’ broke down between Sparta and Athens and the Second Peloponnesian War broke out in the 431 BCE when he was a young man–it was this war about which Thucydides writes. In the the tenth year of the war a further peace agreement was reached between Sparta and Athens which was to have lasted for fifty years, but discontent among the allies and subjects of the two major powers created a further period of chaotic intrigue and outright war that voided the treaty between Athens and the Lacedaemonians. The brief truce of c 425-421 BCE between the two major powers is referred to as the ‘Peace of Nicias’, when for a brief time, Athens and Sparta were on friendly terms. ‘[T]he foremost candidates for power in either city, Pleistoanax, son of Pausanias, king of Lacedaemon, and Nicias, son of Niceratus, the most fortunate general of his time, each desired peace more ardently than ever… …they concluded the treaty and made peace, each of the contracting parties swearing to the following articles:‘ (Thuc., bk. I ch. IV, bk. V ch. XV).

It is interesting to note that the dramatic date for Plato’s T&C dialogues is widely thought to have been about 425-421 BCE. This date is so close to that of the Peace of Nicias as to allow the possibility that the dialogues presented by Plato represent events that occurred in Athens during this brief time of peace.

The Characters

In Socrates opening remarks he characterises his guest speakers as follows:-

And thus people of your class are the only ones remaining who are fitted by nature and education to take part at once both in politics and philosophy. Here is Timaeus, of Locris in Italy, a city which has admirable laws, and who is himself in wealth and rank the equal of any of his fellow-citizens; he has held the most important and honourable offices in his own state, and, as I believe, has scaled the heights of all philosophy; and here is Critias, whom every Athenian knows to be no novice in the matters of which we are speaking; and as to, Hermocrates, I am assured by many witnesses that his genius and education qualify him to take part in any speculation of the kind. And therefore yesterday when I saw that you wanted me to describe the formation of the State, I readily assented, being very well aware, that, if you only would, none were better qualified to carry the discussion further, and that when you had engaged our city in a suitable war, you of all men living could best exhibit her playing a fitting part.

(Tim. Jowett translation)

In his dialogues Plato an Athenian, characterises Socrates as the Athenian host, Timaeus of Locri; a Pythagorean philosopher of southern Italy, Critias; an Athenian statesman with a story to tell, Hermocrates; a statesman and soldier of Syracuse on Sicily, and a fourth unidentified guest who is unable to attend due to sickness. The actual existence of Socrates is beyond doubt and Hermocrates who was a prominent citizen and soldier of Syracuse and a major player in the defeat of the Athenian fleet at Syracuse in c 413 BCE is pretty much beyond question. Critias’ existence is well documented as a relative of Plato and the leader of the Thirty Tyrants of Athens. There is however, a great deal of debate over the actual existence of Timaeus of Locri, but there seems to be enough circumstantial evidence in ancient sources to support the idea he was a real person, a Pythagorean philosopher in southern Italy, roughly contemporary with Socrates.

Firstly it is known that Pythagoras a pre-Socratic philosopher–c. 570 – 496 BCE–established a school at Croton in southern Italy c 530 BCE which was dissolved in the second half of the fifth century and was re-formed in Tarentum, the birth place of Timaeus of Tarentum (New World Encyclopedia, Wikipedia) which poses an interesting proposition. As a hypothetical exercise I look at a possible generational connection between Timaeus of Locri and Timaeus of Tauromenium (in Sicily), a well documented historian, born c. 350 BCE–about the time of Plato’s death–and died after 264 BCE. Timaeus of Locri, Italy, and lived ca. 420/380 – ? BCE (Lampert and Planeaux, 1998). If the dates for Timaeus of Locri have any basis in fact, the historian of Tauromenium could well be the great-great grandson of Timaeus of Locri. This would accord with the tradition of naming a child after his grandfather. It would therefore logically follow that Plato’s Timaeus could well have been a real life Pythagorean philosopher. Given the fact that all other characters in the dialogues are at least based on real people, it seems incongruous that Timaeus was the only fictional character involved in the dialogues, so perhaps he should be taken at face value.

Critias was an Athenian and a relative of Plato, and given the historical time-frame for his active political life, could well have been involved in any diplomatic proceedings between Athens and the western colonies. Furthermore, it would make sense if this Critias was one and the same as the leader of the Thirty Tyrants after the end of the Peloponnesian Wars, installed in the position of leader of a new political system established by the victorious Spartans.

Hermocrates who died 408/407 BCE (Britannica) was a highly regarded statesman. Thucydides, Ch., XX in Bk. VI says ‘Hermocrates, son of Hermon, a man who with a general ability of the first order had given proofs of military capacity and brilliant courage in the war‘ and throughout the history of the Peloponnesian War, Hermocrates is referred to with respect and admiration. Plato likewise would have regarded Hermocrates highly and would originally have been pleased to have him theorise on the principals necessary to re-establishing a new, ideal colony as should have been the case with Syracuse after the destruction of the war. Although Hermocrates was highly regarded, the city-state of Syracuse itself would have been a very poor example of an ideal society; and so a new model was needed for the establishment of an ideal state. As stated previously, many scholars believe the Laws contained the subject originally to be expounded by Hermocrates.

The Fourth Man

Socrates opens the dialogue by enumerating the guests present as follows: ‘One, two, three; but where, my dear Timaeus, is the fourth of those who were yesterday my guests and are to be my entertainers to-day? ‘ To which Timaeus replies: ‘He has been taken ill, Socrates; for he would not willingly have been absent from this gathering’ (T&C Jowett translation).

In trying to determine who the absent guest was, Laurence Lampert and Christopher Planeaux (1998)–in Who’s Who in Plato’s Timaeus-Critias and Why–suggest ‘Alkibiades, who dreamed of imperial conquest and who, in the view of Thucydides himself, possessed the talent to make the dream real, must be the absent fourth in Plato’s depiction of a whole cosmos within which great human undertakings occur… …Who but the brilliant young architect and moving force of that expansion of Athenian glory which the Sicilian expedition was meant to be? Who but Alkibiades?‘ Lampert and Planeaux continue, ‘then we are led to conclude that Plato, by beginning these paired dialogues with Socrates’ ostentatious flaunting of one absent interlocutor, points to the absence of that one individual who could have played the pivotal role in the great Athenian imperial events to come and whose attentive presence at a conference like this–were it only possible–might have made all the difference‘ (Lampert and Planeaux, 1998). This might make sense in the context of Athens displaying its supremacy over Hellas, but in my opinion, this was not the intended theme of the Dialogues in the light of Athens’ humiliation and loss of power at the time.

Plutach (c. 46-120 ce), has a less high opinion of Alcibiades expressed in his Comparison of Alcibiades with Coriolanus, in Parallel Lives with the words; ‘All the sober citizens felt disgust at the petulance, the low flattery, and base seductions which Alcibiades, in his public life, allowed himself to employ with the view of winning the people’s favour; and the ungraciousness, pride, and oligarchical haughtiness‘ and he was ‘unscrupulous as a public man, and false.’ This being the commonly held view of Alcibiades, it’s unlikely that Plato would hold him up as an exemplar of virtue and high morality.

The mood of T&C seems far more conciliatory and diplomatic. Furthermore, the dramatic date for the dialogues, c 425-3 BCE fits within the time of the Nicias peace treaty between Athens and Lacedaemon; and for this reason it seems more feasible that the mystery guest would hale from Lacedaemonian Sparta or the Peloponnesian colonies to the west whom Athens wished to enfold. This view is, I think, implied by the inclusion of Timaeus and Hermocrates from the western colonies; former enemies, but now being wooed by Athens.

The fact the dramatic date for events in his dialogues were very recent history and occurred during his lifetime, suggests a certain freshness to Plato’s understanding of the situation. Even if the dialogues were written about forty years after the dramatic date, we can assume the symbolic meaning of the events was not lost on Plato, and fit within the context of his ideas of what was required to create a better form of government in a better society. It is not at all necessary for the details to be absolutely correct, but the significance of the broad schemes would certainly have been pertinent. The characters in the dialogues would have been chosen for their significance in the context of Plato’s vision; to this end, the most likely candidates for the job might be found among the signatories of the Nicias peace treaty. Thucydides names all who took part in the establishment of the treaty; the Lacedaemonian candidates are:-

1). The son of Pausanias, Pleistoanax, an Agiad King of Sparta who reigned from 458–409 BCE–who died about five years before the end of the Peloponnesian War. He was exiled between 446 and 444 BCE, for taking a bribe and later suspected of tampered with a Pythian prophesy. His enemies still blamed him for Spartan disasters. So he is a possible, but not very likely candidate as the fourth guest.

2). Agis II, birth date unknown, he died c. 401 BCE. A Eurypontid king of Sparta, he ruled with his Agiad co-monarch Pausanias. Agis succeeded his father Archidamus in 427 BC, and reigned a little more than 28 years. In 426 BCE, he lead an army of Peloponnesians to invading Attica but was deterred by earthquakes. In 425 BCE he led an army into Attica, but quit fifteen days later; probably due to the possibility of a peace treaty with Athens to which he was a signatory; this makes him a possible contender as Plato’s fourth guest.

3). Ischagoras, Menas, and Philocharidas were Lacedaemonian envoys, each of whom seem not to have been particularly distinguished, and so, unlikely as candidates.

4). Cnemus, was a Spartan high admiral in the second year of the Peloponnesian war, 430 BCE. From a reading of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, Cnemus’ career was not particularly distinguished; this makes him an unlikely fourth guest.

5). Another possibility for the absent fourth man in the T&C dialogues is Alcibiades, born: 450 BCE, in Classical Athens, and assassinated in Phrygia 404 BCE – son of Cleinias, a prominent Athenian statesman, orator, and general. Alcibiades seems to have been the obsession and love interest, and a lifetime acquaintance of Socrates; as such, he should be considered a possible candidate for the missing character in the dialogues. And he was certainly involved in the turbulent interstate politics of Greece for most of his life, carrying a deep mistrust of the Lacedaemonians (Spartans). Alcibiades would have been between 26-30 years old at the dramatic date between 425 BCE (Lee, 1965) and 421 BCE (Lampert and Planeaux, 1998); the 39th-43rd year of the war.

If Timaeus and Critias was intended as the dramatisation of an event aimed at reconciling differences between diverse warring parties; would the Athenians deliberately out-number representatives from other interested states with Critias and Socrates already present? We have a potential representative from Syracus, one from Italian Lokris, it seems logical to have a representative from Lacedaemon which introduces another possibility.

6). Tellis was a signatory to the Peace of Nicias in 421, but his son Brasidas is of greater interest. Brasidas’ date of birth is unknown but he died 422 BCE. He was the most distinguished Spartan officer during the first decade of the Peloponnesian War. Brasidas also distinguished himself in the assault on the Athenians during the Battle of Amphipolis during which he was severely wounded and eventually died (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, bk. V ch. XV). To my mind Brasidas is the best candidate for Socrates’ fourth guest.

But for his recent death from war injuries c 422 BCE very close to the dramatic date of the Dialogues and the Nicias peace treaty, Brasidas would certainly have been included in negotiations for peace. There is no-one who is treated by Thucydides with more admiration and respect, for his military brilliance, his intelligence and high ideals as was Brasidas. The dramatic inclusion of someone of this calibre as the fourth guest in the Dialogues, must have been profoundly desired by Plato and therefore, needed a dramatic device to include the principals Brasidas represented into the intended over-all scheme of the dialogues.

The themes of the intended dialogues are: 1) Timaeus addressing a contemporary cosmological view of the world and the nature of existence; 2) Critias presenting his story of the folly, hubris and aggressive ambition of the Atlantians that went to war against Athens; sins of which Athens itself was guilty; 3) Hermocrates is widely thought to have been intended to presented the principals expressed in Plato’s Laws which were needed to establish a well governed colony or polis; but he may have been passed over because of the bad experiences Plato later had in Syracuse; 4) From a reading of the Republic, the fourth theme would logically have include the military for the protection of the populace, from both external threats and internal unrest. To this end, the highly organised and disciplined military of Sparta would be the best example, and Brasidas would certainly represent the epitome of Spartan military prowess. (Thuc., bk. I ch. IV, bk. V ch. XV).

Truth or Allegory

When Plato tells us that Critias’ story is true–no less than seven times–why is there so much resistance to the idea that he believed he was telling the truth? Throughout his works Plato was always very careful to distinguish between the imagery/allegory and truth. It does not follow that a man so careful about how he was understood, would try to deceive an audience concerning the veracity of any story, particularly one that involves a family connection. The word “image” is perhaps one of the most frequently used by Plato, and is often accompanied by the concepts of meaning, truth or falsity and is often used in the way we would say in modern times, “picture this” so he was very much aware of the difference between representational imagery and what he deemed to be actual fact or truth and the need to be clear in one’s meaning:-

1). The Republic book II, The Individual, the State and Education; Socrates says to Adeimantus in speaking of the battles of the gods in Homer, he says; ‘these tales must not be admitted into our State, whether they are supposed to have an allegorical meaning or not. For a young person cannot judge what is allegorical and what is literal; anything that he receives into his mind at that age is likely to become indelible and unalterable; and therefore it is most important that the tales which the young first hear should be models of virtuous thoughts.‘

2). The Republic, book VI, The Philosophy of Government; Socrates in reply to Adeimantus’ several questions;- ‘You ask a question, I said, to which a reply can only be given in a parable… …but now hear the parable, and then you will be still more amused at the meagreness of my imagination‘ and ‘if I am to plead their cause, I must have recourse to fiction, and put together a figure made up of many things, like the fabulous unions of goats and stags which are found in pictures.‘ Socrates asks of Adeimantus: ‘And will the love of a lie be any part of a philosopher’s nature? Will he not utterly hate a lie?‘

3). The Republic book VII, On Shadows and Realities in Education; Socrates – Glaucon:-‘And now, I said, let me show in a figure how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened‘. Socrates says further in summing up the cave of shadows allegory; ‘This entire allegory, I said, you may now append, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument; the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upward to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief, which, at your desire, I have expressed—whether rightly or wrongly, God knows.‘

4). The Republic book X, The Recompense of Life; Socrates – Glaucon:- ‘all poetical imitations are ruinous to the understanding of the hearers, and that the knowledge of their true nature is the only antidote to them.‘ Plato, since his earliest youth held Homer in awe but speaks against what he perceives as fiction with the words; ‘but a man is not to be reverenced more than the truth‘.

5). Letter VII – Plato to Dion’s associates and friends: ‘Now in subjects in which, by reason of our defective education, we have not been accustomed even to search for the truth, but are satisfied with whatever images are presented to us, we are not held up to ridicule by one another‘.

How can it be that Plato, author of so many Dialogues and Letters–so fixated on truth, and ensuring as far as possible a clear understanding by his audience of what he is saying–would claim a story to be the truth if it were not so?

The Problem of Atlantis

One of the main problems for modern scholarship is the entrenched attitudes and beliefs about the nature of Plato’s and other’s works that have been developed within the academic community in recent times from the standpoint of a modern world view. Another is the wide spread simplistic, and perhaps, politically correct view that Greeks are Greeks, despite ample evidence to the fact there is a great deal of ethnic diversity on the Balkan Peninsula, particularly in southern Greece; and it is these differences that might present clues to the identities of the protagonists in Plato’s Timaeus and Critias dialogues.

Plato, as everyone before and everyone since, had limits to his understanding of the world in which he lived, and of significant events of the past as handed down by texts or word of mouth. But he was fastidious in his attention to clarity and logic. Therefore, it behoves us to accept what he wrote as well-intentioned and true to the best of his knowledge. It is my belief that the majority of what Plato claimed as true with regard to Critias’ story was in broad principal, true; but there are several anomalous problems arising from a limited understanding of the world to which he was trying to give life. Any analysis of these anomalies and their resultant problems, in the absence of any direct evidence, requires that most, if not all, aspects of Plato’s story of Atlantis be answered by careful consideration of the circumstantial evidences at our disposal and the matching of the patterns of events illustrated by Plato, with patterns of past events as described by modern archaeology, science and enquiry.

Sources

Explanation:- Due to the fact that many sources used in this document are derived directly from the internet, this creates certain problems with the structure of a bibliography. Below is an attempt to list sources in a coherent and logical way. Upload dates are often not given, but encyclipaedic downloads from the internet are all not earlier than 2016.

Anon. Callippus. Perseus. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0104%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DC%3Aentry+group%3D6%3Aentry%3Dcallippus-bio-1

Anon. – Dion: ruler of Syracuse. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dion-ruler-of-Syracuse.

Anon. – Peloponnesian War Timeline. Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/timeline/Peloponnesian_War/

Anon. – Pleistoanax, Perseus, www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0104…pleistoanax

Anon. – Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, New World Encyclopedia, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Pythagoras_and_Pythagoreans

Anon. – Timaeus of Locri (ca. 400 B.C.E.). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Encyclopedia.com. 13 Jan. 2018 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>

Anon. – Wikipedia, Callippus, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Callippus

Cartwright, M. (2013, June 01). Peloponnesian War. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.ancient.eu/Peloponnesian_War/

Lampert, Laurence; Planeaux, Christopher. 1998. Who’s Who in Plato’s Timaeus-Critias and Why. The Review of Metaphysics, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/WHO%27S+WHO+IN+PLATO%27S+TIMAEUS-CRITIAS+AND+WHY.-a053868362

Meinwald, Constance C. 2016, Plato: Greek philosopher – Encyclopaedea Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Plato

Plato, The Complete Works of Plato, compiled by Dr Mohamed Elwany, 2017. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, (1817-1893) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammed_Elwany. Pasim (Open source internet).

Plato 360 BCE, Critias, Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Pasim (Open source internet).

Plato, 360 BCE, The Seventh Letter (to the relatives and friends of Dion) Translated by J. Harward. Pasim.

Plato 360 BCE, Timaeus, Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Pasim. (Open source internet).

Plato, Timaeus and Critias, translated by Desmond Lee, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1977.

Smith, William Ed. Callipus A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology / Callippus. Pasim.

Thucydides, c 411BCE The History of the Peloponnesian War (431 BCE), Translator: Richard Crawley 2009. [EBook #7142] (Pleistoanax, bk.I ch.IV, bk. V ch.XV) (Peace of Nicias, bk.V ch.XV).